|

|

| << PREV |

|

|

It is essential for evolution to become the central

core of any educational system, because it is

evolution, in the broad sense, that links inorganic

nature with life, and the stars with the earth, and

matter with mind, and animals with man.

Human history is a continuation of biological

evolution in a different form.

SIR JULIAN HUXLEY, 1959

(Tax and Callender 1960, 3:42)

The previous chapters have spanned history from the Greek philosophers to Darwin, and have passed into this present day showing history to be a series of ever deepening confrontations between opposing ideologies. As pointed out in Chapter One, the first of these ideologies consists of the belief in the existence of a Supreme Being and the concomitant belief in the survival of human consciousness after physical death. While there is no proof for either, these are mankind's most basic and deep-rooted beliefs. Throughout history, and even to this present day, the majority of people have believed in an afterlife, no matter how hazy their concepts of this personal future, while there is among most the belief in a Supreme Being who created man, gave him rules to live by, and is interested in the management of human affairs. Over the past few generations, many of the details of this scenario have been lost or forgotten, but the essence of the idea still remains firmly entrenched in the human consciousness. The written source of these concepts in Western society is recognized to be the Bible which, it is believed, is God's revelation to man of those things that would otherwise be unknowable. The origins of the universe, planet earth, and life itself are among those mysteries unknowable except by revelation.

The opposing ideology, in its extreme, relies solely on what is demonstrable

to the human senses. Thus it denies a conscious existence after physical

death and the existence of a Supreme Being. It logically follows that there

is no divine Law-giver, no Judge, and no would-be Master of human affairs.

Naturally, there is a spectrum of beliefs between these two philosophical

positions, while the typical view of many today was expressed by Albert

Einstein, when asked about his views on God: "I believe in Spinoza's God

who reveals himself in the orderly harmony of what exists, not in a God

who concerns himself with the fates and actions of human beings" (Hoffman

1972, 95). This is not only Spinoza's God, but, it will be recalled, was

also Aristotle's. When pursued to its ultimate conclusion, this common

view places God as a disinterested party, leaving man without rules and

thus without accountability, destined to manage the world in which he lives.

In a nutshell, this is the view of the humanist today.

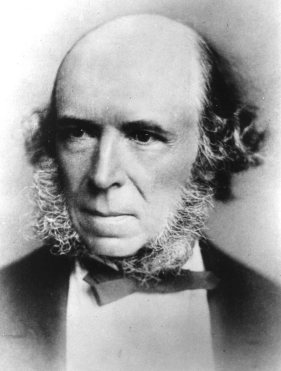

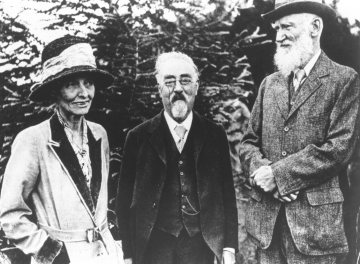

Julian Huxley, 1887-1975. Grandson of T. H. Huxley but without his forebear's mastery of rhetoric; he nevertheless carried the atheist banner further by quiet strokes of the pen than by debate. (Photograph by Godfrey Argent for the National Portrait Gallery, London; Miller Services) |

Humanists are a steadily increasing and influential minority,

quite sincere in their dedication to bring about world unity and peace

through intelligent human management. They argue, not without some justification,

that, historically, theistic religions have been responsible for the dissension

between nations, and that in today's crowded and complex world it is vital

to eliminate this source of division. Ultimately, the humanist aim, as

set forth by the second Humanist Manifesto, is to eliminate national sovereignty

itself in order to achieve a new world order (Kurtz and Wilson 1973, 4).[1]

One of the principal architects of world humanism in this century was Julian

Huxley, biologist and grandson of Thomas Huxley. As first director general

of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

(UNESCO), which is the body that attempts to monitor, if not control, all

that enters the human mind, Julian Huxley in his framework policy included

the following aim:

Thus the general philosophy of UNESCO should it seems, be a scientific world humanism, global in extent and evolutionary in background. Evolution in the broad sense denotes all the historical processes of change and development at work in the universe. It is divisible into three very different sectors: the inorganic or lifeless, the organic or biological, and the social or human (J. Huxley 1976, 16).[2] |

We have seen in the previous chapters that Lyell provided what was seen to be evidence for inorganic evolution; Darwin provided the parallel evidence for biological evolution; and Herbert Spencer, their Victorian contemporary, laid the groundwork for the more subjective area of social evolution. This brings us now to the social sciences as the third leg of the evolutionary structure that supports the humanist worldview.

The social sciences are generally recognized to be the least rigorous

of scientific disciplines and have certainly provided the seedbed for many

of the most flagrant examples of prejudice in the name of science. Classic

examples of the search for evidence of evolution of human intelligence

were given in Chapter Ten, but further aspects of the social sciences need

to be brought to light in order to evaluate this somewhat hollow third

leg.

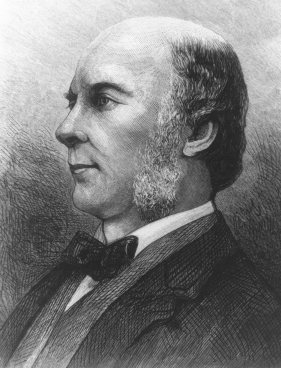

| Latter-day Law-giver

Herbert Spencer was quite clearly eccentric. The lone survivor of nine offspring, from chronically alienated parents, he was the living example of his own maxim that evolutionary progress is made by "survival of the fittest". Spencer's "fitness" was, he believed, a superhuman intellect, which brought together, for the benefit of mankind, a perfectly axiomatized system of all knowledge, from the evolution of the galaxies to the evolution of human ethics, morals, and even emotions. He had rejected all ideas of the supernatural at an early age. From a mechanistic viewpoint he saw developmental (evolutionary) adaptation in every conceivable discipline (Spencer 1904, l:151ff). He was even convinced that all previous philosophers had become "adapted" to their environment and claimed that their thinking was thus colored by the society in which they lived. Spencer chose to be different and deliberately kept himself apart from society. He never married, was most argumentative when in company, and, as is often the case with individuals of this type, could be observed absent-mindedly talking aloud to himself in public (Spencer 1904, 1:174). This was the self-taught, self-confessed genius who between the years 1860-96 produced the Synthetic Philosophy, a mammoth dissertation on all human knowledge -- in ten volumes. The tragedy was that for all this effort, and there were other works besides the Synthetic Philosophy, he had selected his facts to fit the theory and was seemingly totally blind to facts that did not fit (Irving 1955, 237).[3] |

Herbert Spencer, 1820-1903. Eccentric armchair philosopher wrote prolifically and convinced many Victorians of his evolutionary approach to the social sciences. (Photograph by Lalonde; Library of Congress, Washington) |

Spencer introduced the expression "survival of the fittest", in his

Principles

of Biology (1864). Although the Biology was generally out of

favor with the true Darwinist because of Spencer's sympathy to Lamarck's

ideas, Darwin himself was somewhat double-faced in the matter. First, he

was pleased to lift the expression "survival of the fittest" directly from

Spencer's Biology and incorporate it into the fifth edition of the

Origin (Darwin 1869, 92). Second, it seems that by 1868 Darwin had

recognized that chance and chance alone -- that is natural selection --

was insufficient to account for the origin of new species. He could not

accept teleology as a mechanism, since this bordered on the supernatural,

and the only recourse left was an appeal to Lamarck's theory on the inheritance

of acquired characteristics. But to accept any Lamarckian concept would

severely reduce in stature his precious natural selection. Nevertheless,

Darwin did just that, although this transgression of the father is seldom

mentioned in commentaries by the faithful. Vorzimmer (1963) points out

that, on reading the Biology, Darwin lifted Spencer's Lamarckian

notion of "physiological units", called them "pangenes", and incorporated

the idea as his own "Provisional Hypothesis of Pangenesis" in his Variations

of Animals and Plants Under Domestication (Darwin 1868, 2:357).[4]

Throughout Darwin's writings, particularly those of his later years, shades

of Lamarck can be detected. A wonderful passage, deleted from his autobiography,

written in 1876, will serve as an example not only of his Lamarckian leanings

but as an insight into his irreligious nature:

Nor must we overlook the probability of the constant inculcation in a belief in God on the minds of children producing so strong and perhaps an inherited effect on their brains not yet fully developed, that it would be as difficult for them to throw off their belief in God, as for a monkey to throw off its instinctive fear and hatred of a snake (Barlow 1958, 93).

It would seem that the psychologists are less cognizant or, perhaps

less critical, of the long discredited Lamarckism, because Spencer's speculative

Principles

of Psychology (1870-72) elevated him to the title of forefather to

the functionalist school of psychology (Zusne 1975, 124); in this work

he claimed that man had evolved emotionally as well as physically, thus

emphasizing the continuity from animal to man. Continuing in the same speculative

vein, his final work on the Principles of Ethics (1893) maintained

that man's laws evolved as societies became more complex. This is held

to be true today, in spite of the fact that a system of jurisprudence given

to desert tent dwellers in the fifteenth century B.C. is still the best

system and has been maintained in Judeo-Christian countries thirty-five

centuries later.

Spencer was never more than an accomplished amateur in the sciences

and had little knowledge of history, with the result that specialists in

the fields of history, science, and philosophy were not impressed with

his efforts. The principal criticism was directed against his "deductive"

method, where he inferred subtle laws from vague first principles and then

selected material from the literature to illustrate these laws. Darwin

strongly objected to Spencer's methods (Barlow 1958, 109). Nevertheless,

Spencer evidently wrote what some wanted to read, and by the 1890s he was

internationally famous, having had great influence on nineteenth century

thinking. Ironically, in spite of his complete rejection of Christianity,

it was theChristian Spectator in England that elevated him to almost

supernatural status in writing: "Like Moses, when he came down from the

Mount, this positive philosophy [evolution] comes with a veil over its

face, that its too divine radiance may be hidden for a time. This is Science

that has been conversing with God, and brings in her hand His law written

on stone" (Kardiner and Preble 1961, 42).

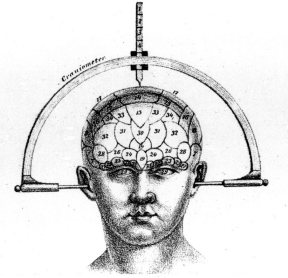

Franz Joseph Gall, 1758-1828. Viennese-born physician living in Paris believed the human brain was physically developed according to its use and began the fashionable (and lucrative) practice of phrenology -- determination of an individual's potential by feeling bumps on the head. This pseudoscience later led to the idea that brain size is directly related to intelligence (Academy of Medicine, Toronto) |

As with many "great works" based on speculation, Spencer's contribution to the wisdom of mankind was destined to be short-lived. Nevertheless, the notion that morals and ethics have evolved imposed itself on the thinking of the day, for whether there is evidence to support it or not, if biological evolution is true, then there must have been a gradation from the amoral to the moral as animal became man. More than half a century of anthropological inquiry, often with questions unwittingly slanted to elicit the desired reply, has naturally given confirmation of that expectation. This being so, it is then argued that our highly civilized state today has come about by a continual and progressive change of mores, and it is incumbent on today's leaders to direct that continuing change in order to produce a more perfect global society tomorrow.[5] Examples of this very thing are numerous, and anyone with a memory span of a decade or more can recall, for example, that though lotteries were once considered immoral and were illegal, they are not so today. Then again, the death penalty for murder was abandoned in the belief that civilized man had evolved beyond having to impose this primitive sentence. Somehow the question was never raised about the evolved status of the murderer. While Spencer's legacy to mankind is evidently quite hollow, its conclusions had been given substance by Darwin, and we clearly see the outworkings today. However, there are other avenues of the "fuzzy" social sciences that also take their substance from Darwin and need to be brought into the light of day. |

Nature or Nurture?

The perennial question on the new parent's mind is, Will little Willie take after his mother, his father, neither, or both? Only time can tell, it seems, yet there has been a divided opinion over this problem of the origin of human personality ever since thought was first given to it. Some would argue that the infant is born as a blank sheet on which the environment writes, and that it is therefore the quality of nurture that determines our ultimate personality. Others have argued with equal conviction that our personality is determined genetically through immediate parents and ancestors, and that it is therefore nature that is the controlling factor; environment, in this view, is thought to play little or no part.

Today, responsible scientists concede that both heredity and environment

-- nature and nurture -- play important parts, but during the past century

or so, the opposing schools of thought not only produced several intellectual

scandals of major proportions but also were directly responsible for the

extermination of millions in the Nazi gas chambers. The "nature" school,

which maintains that heredity molds behavior, is known as biological determinism

and began with Francis Galton.

| Galton's Inheritance

Francis Galton was the younger cousin of Charles Darwin and an independently wealthy member of England's upper class (Cowan 1969). As a child prodigy, he had developed an obsession for quantifying every conceivable human act, and in 1859, the year of the publication of Darwin's theory of evolution and Broca's theory of brain size, Galton immediately became convinced of both. It will be recalled from Chapter Ten that French physician Paul Broca had maintained that human intelligence was directly related to brain size and, consequently, to the size of the head. This seemingly permitted intelligence to be measured directly with calipers and tape measure. Chapter Ten also pointed out that this notion was Lamarckian and had influenced Darwin's thinking on the question of mentality. Darwin (1868, 2:357) came to believe that inheritance took place by a blending mechanism, and Galton (1897) later developed this into a law.[6] Galton's law stated that an individual's total personality is the sum of all ancestors, consisting of a quarter from each parent, plus a sixteenth from each grandparent, and so on. Environment had no part in Galton's law. However, this entire mathematical edifice collapsed -- or should have collapsed -- with the "discovery" of Mendel's genetics in 1900 (his findings were actually first published in 1865). Nevertheless, in the 1860s Galton began his lifelong quest to quantify human nature. In this attempt he added somewhat to Broca's theory by expanding "intelligence" to mean a number of intangible behavioral qualities. For instance, a highly intelligent individual would also be highly moral and, conversely, those of low intelligence would be "wayward". Naturally, examples could always be found to support this simplistic notion, and Galton made great use of this device, steadfastly ignoring instances that did not fit the expected pattern. |

Francis Galton, 1822-1911. The mechanistic world of Francis Galton would reduce every one of man's functions to a number and be treated statistically. He was fully convinced that nature's survival of the fittest principle applied to man and should be under the control of some elitist group. (Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library Board) |

The full title to Darwin's Origin reads On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. The word "races" in the subtitle led to many social inequities between the leaders and the led and between ethnic groups, causing much class distinction, all justified on the basis of the new-found biological science (Hoffstader 1944). Darwin had used the word "race" to mean variants within the species, but this eventually came to include man and raised the question, Whom did nature wish to preserve? White man or black? Christian or Jew? Protestant or Catholic? The possibilities for subdivision were limited only by man's actual prejudices. This was the basis for what became known as Social Darwinism, in which the class structure was assumed to be fixed by the laws of nature. It was thus biologically impossible, for example, for a laborer's son ever to aspire to any better station in life, and vestiges of this nineteenth century class distinction can still be seen today in the British Rail system.[7]

Francis Galton played no small part in all this, since he firmly believed that within the English nation there was a genetically superior stock, inheritable and manifested as the most eminent families. In 1869 Galton published Heredity Genius, a study of the variability of the human intellect through the biographies of great men -- he included the Darwins. Other works followed in which he introduced the term "nature and nurture", allowing for the effects of environment, but throughout he remained a convinced hereditarian, emphasizing that all that we are is the result of inheritance. As time went by, however, it gradually became evident that acquired intellect cannot be passed on to the next generation, and by the turn of the century Mendel's laws made the reason clear: the genetic material that we pass on to the next generation is determined at the time of our conception and cannot be influenced by subsequent events in adulthood. Accordingly, Galton then shifted the argument slightly, eliminating the need for "acquired characteristics". He was now left with the claim that certain races were inherently superior and that their superiority was fixed forever from the past as well as into the future. Although this raised the obvious and very awkward question concerning the interfertility of the races, purportedly originating from different sources, this issue never seems to have bothered Galton or his racist followers. The conclusion to Galton's argument then followed that, for the sake of mankind's future, pollution of the precious superior gene pool by interbreeding with inferior stock had to be stopped at all costs.

It was but a short step from this conclusion to suggest that measures should be taken to intelligently direct man's evolutionary progress rather than leaving such a vital matter to random chance. "Judicious marriages" of the superior stock of human beings over "several consecutive generations" would, Galton proposed, produce a "highly gifted race of men" (Galton 1869, 1). It was an obvious final step to propose active discouragement of breeding by the inferior stock and so raise the general level of intelligence and morality of a whole nation. Galton had utterly rejected the Christian doctrine and wrote openly about this; he had no qualms about speaking of controlled breeding of the human race in the same breath as breeding dogs and race horses (Galton 1869, 1; Russell 1951, 49).[8] Getting these racial notions accepted by the scientific community of the day was another challenge, especially since psychology at that time was held to be a philosophy rather than a science. However, by working in cooperation with the mathematician Karl Pearson, Galton applied a number of refined statistical techniques to his anthropomorphic measurements. With numbers and formulas to grace the pages of publications, psychology thus took upon itself the appearance of a scientific discipline, the diminished comprehensibility serving greatly to increase credibility. Exactly the same approach has been used more recently, and seemingly for the same purpose, by Harvard's sociobiologist Edward O. Wilson, working with physicist Charles Lumsden (Lumsden and Wilson 1981).[9]

Galton's next step to gaining acceptance by orthodox science was to coin the name "eugenics" from the Greek; the term means "wellborn". Here was the science to produce the Utopian dream of a super-race to control tomorrow's world. The dream began to be realized in 1901 with the founding of the Eugenics Education Society, based at the statistics department of University College, London. Galton lived to see the Eugenics Society eventually become a flourishing political movement, while the work on which it was all founded, the calipers and stopwatch (to measure reaction times) applied to the heads of idiots and criminals, was given scientific respectability in the professional journal Biometrika, founded and edited, of course, by Galton and Pearson.

Before Galton died in 1911, some of the scientific community had evidently

become convinced. He received many honors, including the Darwin and Wallace

medal, the Copley medal, the Huxley medal, and a knighthood. However, divine

retribution forbade that he should live to fulfill his own eugenic obligation.

Scion of two prominent English families, married to the daughter of a third,

Sir Francis Galton had died without issue.

Galton's Legacy

The reader should not be misled and imagine that Darwinian honors and a knighthood were bestowed because there was any scientific merit to Galton's work. It was, we should remember, shown to be fundamentally unsound on several grounds (Cowan 1969, 9).[10] First, as pointed out in Chapter Ten, intelligence cannot be determined by the size of the head, and in Galton's day there were a mounting number of cases of ignorant men with large heads and brilliant men with small heads. Second, Mendel's work on genetics was beginning to be accepted in 1900 and showed that neither intelligence nor any other acquired characteristic can be passed on genetically. Finally, as early as 1892, Boas had demonstrated that lack of adequate nutrition and proper sanitation facilities not only retards physical growth of children, but also retards their mental faculties (Boas 1892).

The effect of nurture denied by Galton is thus crucial. This has been

confirmed many times since; laziness, for example, was thought to be an

inherited trait until real science located hookworm as a culprit (Williams

1969).[11] Given these

facts and the general belief in the biblical description of mankind as

originating from a single mating pair (Galton's inherent racial superiority

required multiple mating pairs), it was incredible that the knighthood

should have been awarded as late as it was, in 1909. Only the previous

year the Hardy-Weinberg law concerned with population genetics had been

introduced, which put the final nail in Galton's eugenical coffin (Hardy

1959). The only positive aspects of Galton's work were the development

of statistical techniques and his work on fingerprints, neither of which

would seem to justify all the approbation. Clearly, the honors were awarded

for his gallant though misguided attempt to usher in the brave new world

with calipers and ruler, not for any genuine contribution to science.

I.Q. and Sterilization

Craniometry, or the measurement of heads, was a serious scientific occupation

just over a century ago; seven million school children in Germany, for

example, submitted to this pseudoscience as part of Rudolph Virchow's quest

to find a distinctly German racial type -- the results showed that there

was no such thing (Ackerknecht 1953). In France Alfred Binet measured the

heads of many schoolchildren and criminals, but finally came to the honest

conclusion that any craniometric differences there may be between a group

of intelligent children and a group of normal children were too small to

be significant.

An illustration from Thomas Sewall's 1837 lectures on phrenology showing the use of the craniometer. Originally intended for the determination of personality, its use was eventually confined to the measurement of intelligence and assessment of "racial characteristics". (Academy of Medicine, Toronto) |

What was just as important, however, was Binet's realization that the measurements themselves were very much influenced by the expectations of those making the measurements. As we have seen in previous chapters, preconception did produce an unconscious bias, which, in this case, happened to be the most significant factor in the analysis. Binet then set out to develop an alternative approach to quantifying intelligence, not based on a Lamarckian concept, but based more rationally on the intellect itself. The method consisted of a series of test questions on a wide range of topics requiring only simple answers that could easily be reduced to a single number. Thus was born, in 1908, the concept of the Intelligence Quotient, familiarly known today as the I.Q. test (Binet and Simon 1973; Stern 1914).[12] Binet never claimed it to be anything more than a means of sorting out those who were not average, and this would apply to the very bright as well as to those with problems. There were enthusiasts, however, who took Binet's work as a means of grading society according to the I.Q. score, and since intelligence was still firmly held to be racially inherent, this meant that the overall intelligence of the nation could be improved by preventing those near the bottom of the scale from making a genetic contribution. This was surely a noble evolutionary aspiration, and the American psychologist Henry Goddard (1866-1957) was its principal advocate and crusader, while the Rockefeller foundation provided the funding. Now while idiots and imbeciles are clearly not normal people -- that is, even when afforded every opportunity these individuals are mentally incapable of mastering full speech or the written language -- there will always be a complete spectrum of people in between, from the level of the imbecile to that approaching the level of the normal person. This group has traditionally been referred to as the "feeble-minded" and poses the problem of where to set the limit on who should and who should not be allowed to reproduce. |

For the committed eugenicist, however, playing the role of God posed no problem, and Goddard's (1914) vigorous propaganda campaign convinced the American people that the nation was being threatened by the "menace of the feeble-minded" outbreeding the rest of normal society. Not only was this "human refuse" (Galton's phrase) said to be generating at an alarming rate within the nation's slums and backwoods, but, it was pointed out, they were actually being imported from Ireland and the Jewish ghettos of Europe. By the 1920s, extensive testing programs had been set up within the American school system to separate the feeble-minded children by means of a modified I.Q. test; this was merely substituting Galton's calipers and ruler with Binet's paper and pencil. Many, if not most, of these feeble-minded children, it must be remembered, were simply undernourished children of the unemployed. Institutions were built whereby the separated children could be made to feel comfortable among their own kind, but above all, the system was organized with the ultimate purpose of preventing the feeble-minded from breeding.

Between 1907 and 1938, sterilization laws were passed in thirty American states, and the surgical operation (tubal ligation for women and vasectomy, or even castration, for men) carried out on a volunteer basis at first, but "voluntary" tended to become "forced", especially for those regarded as degenerate, defective, or criminal. For example, it was a simple matter then, as it is today, to delay the welfare check to the unmarried mother until "voluntary" sterilization had been agreed to -- cooperation was usually assured within a day or two. The dissemination of birth control information and devices among the poor and unemployed during the 1930s was promoted by female libertarian Margaret Sanger.[13] However, she was viewed with suspicion by the orthodox eugenicists, since they felt that the surgeon's knife was the only sure and permanent way of halting another generation of welfare dependents (Douglas 1970).

Half a century later the situation has changed little, except that it

has become more liberal. The law now allows abortion to be included as

a method of birth control, although, strictly speaking, it should be regarded

as death control and be put in the same category as euthanasia.

Finally, it must not be overlooked that the Utopian ideals of the eugenicist

have tended to become politically expedient, especially in a time of high

unemployment. After all, the notion that feeblemindedness is passed on

genetically is still fostered in the attitude that says sterilization today

is a small price to pay to minimize welfare payments tomorrow.

The Road From Darwin to Hitler

Galton had based his ideas of orderly upgrading of the human race squarely on Darwin's evolution. It was argued that, in obedience to nature's great principle of survival of the fittest, only the fittest human beings should be allowed to enter the world; with Galton's laws in hand, mankind was in a position to control human evolution and even produce a super race. On Galton's demise, the prophet's mantle was passed to America and shared among the disciples: Henry Goddard, Henry Fairfield Osborn, Harry Laughlin, and Madison Grant, to name a few. In England, the eugenical banner was being carried by such notables as Leonard Darwin (son of Charles Darwin), Winston Churchill, the Lord Chief Justice, and the Anglican Bishop of Oxford (Chase 1980, 136).[14] There was also a strong following in Germany, and Gasman (1971) has documented in fine detail[15] the steps from Darwin's chief apostle Ernst Haeckel to the German National Socialist Party (Phelps 1963).[16] For example, Haeckel in his Wonders of Life observes (incorrectly) that the newborn infant is deaf and without consciousness, from which he concludes that there is no human soul or spirit at this point. He then advocates "the destruction of abnormal new born infants" and argues that this "cannot rationally be classed as murder" (Haeckel 1904, 21). Haeckel's logic then carried him further, and he noted that "hundreds of thousands of incurables -- lunatics, lepers, people with cancer, etc. are artificially kept alive ... without the slightest profit to themselves or the general body" (Haeckel 1904, 118). He suggested that "the redemption from this evil should be accomplished by a dose of some painless and rapid poison ... under the control of an authoritative commission" (Haeckel 1904, 119).

All this great wisdom from a Darwinian prophet will be recognized as the grist for Hitler's mill. Keith (1949, 230), himself a Darwinian, noted the strong connection between evolutionary theory and the German Fuhrer's objectives.[17] Further direct inspiration has been noted by a recent author, Werner Maser (1970, 77) who shows from his analysis of Hitler's Mein Kampf (1924) that Darwin was the general source for Hitler's notions of biology, worship, force, and struggle, and of his rejection of moral causality in history. More recently still, Kelly (1981) has traced the rise of Darwinism in Germany.

Adolf Hitler was dedicated to the idea of an Aryan super race for millennial rule of the world. He had been profoundly influenced by German translations of two American publications. The Passing of the Great Race, by eugenicist Madison Grant, first published in 1916 and with subsequent revisions, purporting to show how the American nation was being genetically polluted by those unfit to breed. Grant also provided the answer to German embarrassment at having lost the First World War, and Hitler was quick to include this in his Mein Kampf (Hitler 1941, 597). According to Grant, so many of the big, blonde fighting men indigenous to the German nation had been killed in the thirty year war (1618-48) that the German armies of 1914-18 had been insufficiently stocked with their superior blood! (Grant 1918, 184). Hitler's rational answer was, of course, to produce more of this Aryan super race -- and quickly -- for the coming world conquest by the Third Reich. Human stud farms were set up during the 1930s to breed from the select few thousand pure stock that remained; Galton's "judicious marriages" had thereby become reality.

The second publication was Harry Laughlin's unabashed creed written in the early 1920s and spelling out exactly who were the socially inadequate and subject to the sterilization laws. The list had grown well beyond Goddard's feeble-minded people and now included the insane, the criminal, the epileptic, the alcoholic, the blind, the deaf, the deformed, and the dependent, including orphans. Voluntary sterilization laws had been in effect in Germany since 1927, but when the National Socialists, or Nazi party, came to power in 1933, with Hitler as their elected chancellor, little time was lost in adopting not only Haeckel's recommendations for infanticide and euthanasia, but virtually the whole of Laughlin's list of race polluters; these individuals were destined for forced sterilization -- it was no longer voluntary (Popenoe 1934). After the collapse of Hitler's thousand year Reich in 1945, the well-kept German records showed that between 1927 and 1933, about eighty-five people a year were voluntarily sterilized. Under the Nazis, at least two million human beings had been forcibly sterilized at a rate of about 450 per day (Chase 1980, 134). These operations were not carried out by steel-helmeted storm troopers but by civilian medical doctors, while the commission set up following Haeckel's recommendation to dispose of the "utterly useless" consisted of university professors, who stoically made their life-and-death decisions on the basis of a completed questionnaire. Haeckel's "dose of some painless and rapid poison" was the subject of research and development at the laboratories of Degesch chemical company. The most effective agent for dispatching thousands of "worthless race types" was found to be prussic acid gas, which the Leverkusen plant of the chemical giant I.G. Farben produced under the trade name of Zyklon B and sold to the Nazi concentration camps. The company had stockpiled enough of the lethal gas to kill more than 200 million people, more than thirty times the actual number destroyed. One can only wonder how many people would have been left to rule had Hitler's Third Reich actually conquered the world (Sutton 1976, 37).

When the German atrocities were exposed to a horrified world at the Nuremberg trials during the late 1940s, the pseudoscience eugenics took upon itself a very low profile, and lost much of the support it had had among the scientific community. It is still very much alive in the minds of a few enthusiasts, however; an attempt was made as recently as 1969, by Jensen, to revive the myth of innate physiological racial differences, said to be responsible for higher intelligence among white people as compared with blacks (Van Evrie 1868).[18] We should be reminded that the Nazi extermination of six million "racial undesirables" began with the quiet implementation of Galton's eugenics by the medical profession and within a decade had grown to become an "industry" of human destruction.

Before leaving this section, the committed Darwinist, loathe to see

a lifetime's inspiration associated in any way with obvious political despots,

is inclined to raise the objection that Darwinian social science cannot

lead to socialism and certainly should not bear the stigma of Marxism.

Haeckel expressed this argument, typically, by pointing out, "The theory

of selection teaches that in human life, as in animal and plant life everywhere,

and at all times, only a small and chosen minority can exist and flourish,

while the enormous majority starve and perish miserably and more or less

prematurely" (Haeckel 1879b, 93). In short, the political doctrine implied

by natural selection is elitist, and the principle derived according to

Haeckel is "aristocratic in the strictest sense of the word" (p. 93). Now

this was precisely the Fascist ideal of the Nazi Socialist party, that

is, rule by the elite. However, Fascism or Marxism, right wing or left

-- all these are only ideological roads that lead to Aldous Huxley's brave

new world, while the foundation for each of these roads is Darwin's theory

of evolution (Carmichael 1954, 373).[19]

Fascism is aligned with biological determinism and tends to emphasize the

unequal struggle by which only those inherently fittest shall rule. Marxism

stresses social progress by stages of revolution, while at the same time

it paradoxically emphasizes peace and equality (UNESCO 1972).[20]

There should be no illusions; Hitler borrowed freely from Marx. The result

is that both Fascism and Marxism finish at the same destiny -- totalitarian

rule by the elite.[21]

Nolle (1966) has pointed out that Fascism and Marxism have this mutual

bond,[22 ] and a moment's

thought will show that the living conditions under General Franco of Spain

or those in the Soviet Union during the same period were the same -- permanent

rule by the elite, with no free elections, representation, or trade unions,

with censored media and, always, a fear of one's neighbor. The French socialist

promise given in 1793 of liberty, equality, and fraternity could not have

been a greater lie.

Cyril Burt -- Eugenics' Death Knell

In some of his early work, Galton had included the study of twins separated at birth and brought up under different environments. This was a very obvious way of identifying the effects of nature and nurture since the twins would be genetically identical. However, Galton had used his trusty calipers to measure intelligence, and, sure enough, although the twins had received different kinds of nurture, their intelligence was seen to be identical. This confirmed Galton's fondest hopes, and intelligence was thereby held to be strictly an inherited entity. During the 1930s, the English psychologist Cyril Burt, a committed hereditarian and, thus, of the biological determinist school, began to repeat Galton's work with twins, although the discredited calipers were now replaced with modified Binet I.Q. tests. Burt eventually obtained a position with the London County Council and had access to birth records, in which he located a total of fifty-three sets of twins that had, for one reason or another, been separated at birth. His published work, over the years, showed that although their environmental backgrounds were quite different, the mental characteristics of each pair were the same. This was taken to confirm Galton's work. This was a signal victory for those on the nature side of the nature-nurture controversy and amply supported the eugenicist. Burt became the dominant voice in educational psychology in Great Britain, which eventually earned him a knighthood.

When Burt died in 1971, the nagging doubts some had felt regarding the

authenticity of his work gradually became confirmed, and by the time Professor

Hearnshaw, who began as an admirer of Burt, had finished the definitive

biography, it was evident that science had a major scandal on its hands.

Cyril Burt had fabricated research data and invented non-existent colleagues

to write supportive articles in the British Journal of Psychology, of

which Burt was the editor. He had also invented two nonexistent collaborators

and attempted to steal the credit for C.E. Spearman's statistical work

on factor analysis (Gould 1981, 234). For all this thoroughly unscientific

effort, Hearnshaw graciously suggested that Burt suffered from paranoia

(Hearnshaw 1979, 289). The affair discredited the biological determinist

position, should have been the final blow to eugenics (although only time

will tell), and was no doubt gleefully seen as a victory by the rival nurture

school. It is the behavioral determinist "nurture" school that has the

dominant position today (Mahoney 1976).[23]

Wilson's Sociobiology

A year or so before Burt's fraud was exposed, Edward Wilson of Harvard University produced his massive half million word study Sociobiology: The New Synthesis (1975). This was actually a synthesis of a number of other people's ideas, but finished as Wilson's theory, which stated that there is a biological basis for all social behavior in the animal kingdom. This view is firmly based on biological evolution. It proposes that whether insects, animals, or man are considered, there are specific genes that control behavior. Wilson is an acknowledged expert on insect behavior. He spent twenty-six chapters of his book rightfully in this area, but then, in the twenty-seventh, launched out and applied his findings to man. This controversial chapter and, subsequently, an entire book (On Human Nature, 1978), is primarily an extended speculation on the existence of genes for specific and variable traits in human behavior -- including spite, aggression, xenophobia, conformity, homosexuality, and the characteristic differences between men and women.

Wilson began in this study with a question that severely troubled Darwin and concerned altruism among species. By the rules of natural selection, it is dog-eat-dog and only the fittest survive, but, in fact, many creatures cooperate and defend others even at the cost of their own lives. Wilson's proposal was that it was all in the genes. All very complicated, to be sure, but if there can be a gene for altruism, then there can be genes for other qualities, and so we find the list for human behavior. Presently, there is virtually no data to support this theory, but proponents will no doubt be found, evidence apparently supporting it reported, and contrary evidence suppressed. And by the familiar bootstrap technique, sociobiology will become a "respectable" science.

Unlike Galton, Wilson is not a eugenicist and does not suggest inherent

eliteness, although he has been severely criticized by scientist and layman

alike for providing opportunities for eugenicists and overt racists to

use his findings to justify racial discrimination. The eugenicist has surely

had his day, but a more serious consequence of this as yet unproven theory

is likely to be in the area of ethics, since it destroys the concept of

free will. It is perfectly evident from other scientific theories reviewed

in these pages that Wilson's theory does not have to be proven in order

to be accepted -- all that is required is a nucleus of devotees with a

will to believe. It should be possible, after a modicum of acceptance among

the scientific community, for thieves, murderers, and homosexual offenders

to be legally defended from "science" by arguing that.the accused are simply

acting out the dictates of their genes and, therefore, are not morally

responsible for their actions. This may be recognized as Rousseau's dictum

that man is inherently good, dressed in modern guise.

The Nurture Side of the Controversy

Franz Boas (1858-1942) was raised in a Jewish home in Germany by liberal "free-thinking" parents, and he was particularly influenced by his mother, who was something of a political activist in the abortive German socialist revolution of 1848 (Kardiner and Preble 1961, 134). Graduating with a doctorate in physics at the age of twenty-three, he turned to anthropometry, or the measurement of the human body, and received training under the great Rudolph Virchow. Now well qualified, he entered the United States in 1887 and rose to be America's foremost anthropologist. Boas was well aware of the wild racist claims made by the eugenicists, mentioned earlier, and was particularly sensitive to their claims that America was being polluted by "worthless races from Europe's ghettos".

Boas set about conducting a vast study of immigrant parents and children. The first study was carried out in 1891 and demonstrated what hundreds of subsequent public health studies continue to show today -- that the children of poor parents grow and develop at rates far lower than those of more affluent families (Boas 1892). Boas had a running battle with the eugenicists, and this work should have shown that, contrary to their views, environment had a significant effect. With characteristic German thoroughness, Boas continued the research and, in 1912, published the results of a massive work in which he studied the variations in head forms of 17,821 subjects. Eugenicists had argued that the shape of the head was characteristic of "race", but Boas showed that significant differences occurred in head shape between American immigrants (Italians, Czechs, and Jews) and their American-born children, the differences varying directly with the length of time the parents had been in the United States. The changes were all in the direction of the Anglo-Saxon type dominant in that country (Boas 1912). In 1916 Boas pointed out that "the more far-reaching the environmental influences that act upon successive generations, the more readily will be a false impression of heredity be given" (Boas 1916, 472).

An example might be the biceps of the blacksmith, which appear to be transmitted from father to son when the son follows the father in the same occupation; however, diet and even geographical location are also known to have an influence during the growth stage of human development. It was not surprising, then, that beginning with a preconception, the committed eugenicist would be deceived by this kind of evidence, which appears to support the hereditarian notion. The better scientist, Boas, had dug deeper and discovered the truth, which was that the genetic characteristics contributed by each parent are not entirely fixed characters but rather potentialities dependent on the environment for the particular form they will eventually assume.

The nature-nurture controversy should have died with this classic work of Boas in 1916, but, in fact, a recent book by Eysenck and Kamin (1981) shows that the argument still has its protagonists.[24] Some of the prejudice-generated smoke can be cleared by considering peas in a pod rather than people and races (the author is indebted to Chase 1980, 637 for this analogy). All the peas in a single pod are phenotypes grown from a single genotype and, therefore, are related to each other in the same way as human twins. If the individual peas are planted in separate pots and placed in differing environments, some with proper sunlight and water and others in harsh, shady conditions without adequate nutrition, their growth rates and final appearance, as would be expected, will be quite different. Here, the inheritance has been the same, but nurture has caused radical differences in the final result; this is what Boas had shown with his immigrant studies. All is not quite so clear-cut as this example may suggest, however, because unlike the peas, people do not all arrive from the same pod. The other half of this experiment consists of planting different varieties of peas under identical conditions. Where these conditions are good, each resulting pea plant would reach its full potential; some plant varieties, for example, would be taller and some shorter. Where the conditions are poor, some varieties would respond better than others. This is where the eugenicist argues that in the dim and distant past some "peas" originated from an entirely different and superior kind of "plant". The argument is one from silence, but the eugenicist always lives in the hopes that each new fossil man discovery will break that silence.

Now it has to be agreed that there are racial differences, and color is perhaps the most obvious example. The cultural or behavioral determinist school of Boas would certainly have to admit that environment has had no effect on the color of the Negro since he left Africa for the cooler northern climate, six to ten generations ago, and, by the same token, the Dutch immigrants to South Africa have not changed color either. Common experience would also tell us that tall parents tend to have tall children, although, like the peas, if the child is nurtured under impoverished conditions, it will not reach its full potential height.

It should now be evident that both heredity and environment play an

important role. When all is said and done, many parents having two or more

children know that even though they have had a similar genetic makeup and

have been raised in the same environment, there can still be great differences

in appearance, intelligence, and temperament. So far as intelligence is

concerned, below average parents can produce brilliant children and intellectually

brilliant parents can have below average children. This is a common enough

observation yet has evidently passed unnoticed by some of the world's scientific

elite. Nobel prize-winner and life-long Marxist Herman J. Muller advocated

human sperm-banks in 1946. California's Robert Graham has recently put

this idea into practice. Five Nobel prize-winners have contributed to The

Herman J. Muller Repository for Germinal Choice (William B. Shockley

is one admitted donor), and by December 1987 forty-one healthy babies had

been produced (See Broad 1980). The very existence of a human sperm-bank

with the object of perpetuating genius indicates that even those who occupy

the most exalted halls of science are not immune from the type of irrationality

practiced by the eugenicists and the extreme element in the biological

determinist school. We will now look at one or two examples of the cultural

or behavioral determinists who went to the opposite extreme.

Scientific Sanction for Free Love

Margaret Mead was a diminutive twenty-three-year-old graduate student, assigned by Professor Franz Boas of Columbia University to study the adolescent culture of the Samoan people. One of the priorities of this nine-month exercise in the South Sea Islands, begun in 1926, was to attack an idea then popular in Germany and originating from the rival "nature" school. This school argued that the turmoil of adolescence was a biological necessity and, therefore, universal.

Boas maintained that the turmoil evident among Western youth was more

cultural than biological and ascribed its cause, among other things, to

repression imposed by the Judeo-Christian ethic on the adolescent's discovery

of sexuality (Kardiner and Preble 1961, 139).[25

]

The people of Samoa were removed, historically and geographically, from

the influence of the Christian church, and even though there were a few

missionaries and churches, it was felt that the native people were sufficiently

unspoiled, and that the effect of indigenous culture could be separated

out by judicious questioning. Mead studied only sixty-eight teenage girls

and, by a great stroke of luck, discovered, to her satisfaction, and more

significantly to her professor's satisfaction, that indeed there were no

inhibitions against casual "love under the palm trees", and, in consequence,

there were no guilt feelings, and adolescent turmoil was unknown (Mead

1973, 67, 72, 75). This was surely worth a doctorate, while, as a further

accolade, Mead popularized her findings in Coming of Age in Samoa, which

when first published in 1928 immediately became a highly controversial

best-seller. It was still being reprinted forty-five years later.

| Mead's future was assured, and she spent the next fifty years promoting the message that as a result of our code of ethics, which included prohibition of premarital sex and sex with only one life partner within the family unit, Westerners suffer guilt, stress, and adolescent turmoil. She hastened to point out that the scientific evidence shows that happy, graceful lives can be lived with casual family ties and easy sex without signs of guilt or neurosis. Mead became the darling of humanists such as Bertrand Russell (1929, 132) and Havelock Ellis, who cited her work often to promote their own ideas of sexual liberation. She was also the natural ally of those who promoted free education, relaxed sexual norms, and parental permissiveness. Between Mead and Benjamin Spock, the pattern of North American child rearing was radically changed, and the fruits of their labors are now becoming evident in today's divorce statistics. Mead's own modest contribution to these statistics consisted of having had three husbands, which would seem to refute the promise of a happy and graceful life she claimed science showed to be possible with the liberated sexual lifestyle. Ironically, for both science and the alleged happy life, Mead, one of America's leading scientists and a purported Christian, died in 1978 in the arms of a psychic faith healer.[26] |

Margaret Mead, 1901-78. The anthropologist being quizzed by students during one of her visits to an American university in 1968. Her advocacy of greater sexual freedom, legalized marijuana, and two-stage marriages made her a virtual guru on campuses during the turbulent 1960s. (Bob Levin, Black Star) |

In 1983 anthropologist Derek Freeman produced his Margaret Mead and

Samoa: The Making and Unmaking of an Anthropological Myth, in which

he showed that Mead's work had been based on a lie. Mead had reported:

Romantic love as it occurs in our civilization inextricably bound up with ideas of monogamy, exclusiveness, jealousy and undeviating fidelity does not occur in Samoa. Our attitude is a compound ... of the institution of monogamy, of the ideas of the age of chivalry, of the ethics of Christianity (Mead 1973, 79).

Mead's happy picture of Samoan life, gleaned in only a few months,

was of a society in which there were only loose family ties, uninhibited

by paternal authority, and with mere lip service paid to bridal virginity;

she further hinted that forcible rape, when it occurred at all, was unknown

prior to the introduction of the moral trappings of white civilization

(Mead 1973, 70). Freeman had spent half his life studying the Samoan culture

and, in complete contrast, found the Samoans to have always had firm family

ties, to be quite authoritarian, and to strongly maintain a cult of virginity

that forbade premarital sex. Moreover, Freeman more diligently dug up the

rape statistics and pointed out that Mead had evidently not read a local

newspaper, such as the Samoan Times, which regularly reported rape

cases during her stay in 1925-26.

Clearly, Mead's was hardly an objective and scientific exercise. Freeman

charitably suggests that Mead was the unprepared innocent receiving compliant

replies to questions unwittingly slanted to elicit her preconceived views.

This type of bias was constantly to be guarded against and, in Mead's case,

resulted in half-truths, if not pure fiction, presented as fact representative

of the whole. Her doctorate gave the exercise scientific credence, swaying

the minds of liberal educators and any others who had reasons for wanting

to believe. Fifty years later it seems the truth can be told, but, unfortunately,

two generations deluded by this pseudoscience have now set a pattern of

behavior difficult to correct.

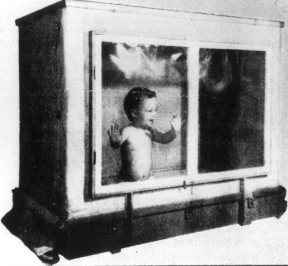

Skinner's baby conditioner in which his daughter spent the first two years of her life being "conditioned". Skinner's attempt to market this device as an "Heir-conditioner" was not successful. (Photograph by Stuart, People Weekly) |

Behavioral Modification

Harvard's Burrhus F. Skinner is one of the most controversial advocates of the nurture school. From 1930 he carried out experimental work with rats and later with pigeons in what became known as the "Skinner box". The box enabled the environment to be controlled while the subject's behavior could be studied in terms of the conditioned reflex. By pressing a lever, the rat could obtain a reward of a food pellet, or the experimenter could administer a punishment by means of a mild electric shock. In this way, much was learned about the learning process and the most efficient means of modifying the subject's behavior was determined. Skinner summarized his findings in The Behavior of Organisms (1938), but within a decade had applied the implication of conditioning principles to society at large in Walden Two (1948), a fictional description of a Utopian community in which education and social regulation are based on rewarding techniques. Some critics saw in this innovation shades of Aldous Huxley's Brave New World, where society was controlled by reward, and greeted the book with fear and dismay. Nevertheless, the Skinner teaching techniques have been widely used for school children, although by use of a teaching machine rather than in a box with food pellets! (Skinner 1979).[27] In addition, by cooperation with drug companies, the effects of certain drugs to aid children with learning difficulties have been studied. Although new understanding has been gained, the whole idea of modifying human behavior in a purposeful way has not been an overwhelming success, and the specter of crossing that fine line, from "aid" to "control" of tomorrow's society in today's classroom, has yet to become a total reality. |

The vision of behavioral modification still has its enthusiasts. For example, in 1978 Sobell and Sobell reported a program to modify the behavior of a group of twenty gamma alcoholics. In this they used the electric shock "punishment" technique. These researchers believed that behavior therapy would enable hard-core alcoholics to become social drinkers, rather than having to become total abstainers. The experiment was widely reported to be successful, and the United States government began to invest considerable sums of money into this new approach. However, an independent study of the same twenty patients in a ten-year follow-up showed a totally different picture with only one success (Pendery et al. 1982). This is another scandal, and the most charitable conclusion would be that, like Burt and Mead, the theory in the minds of the Sobells assumed greater importance than the facts.

As in the case of biological determinism (nature), behavioral determinism (nurture) also denies the free will, since this says, in effect, that we are simply a product of our environment rather than a product of our genes. Clearly, both factors are important, but even then the human psyche involves far more than mere machine response to a combination of biological and environmental circumstances. It would be extremely difficult for humanistic psychology, however, based as it is on evolution, to acknowledge a spiritual dimension to man; this opens up a philosophical minefield involving the destiny of souls, for instance; as mentioned in the opening chapter, the committed humanist cannot accept such a view.

During the past century a great deal of serious work has been done in

the field of psychology, and it would be wrong to leave the reader with

the impression that the social sciences are little more than schools for

scandal. Nevertheless, it has been necessary here to expose some of these

extreme views because of their importance and to give some hint of what

constitutes the third leg of the evolutionary structure that supports today's

doctrine of secular humanism.

Secular Humanism

In the broadest sense, humanism is any view that recognizes the value and dignity of the individual and seeks to better the human condition; none should fault this noble aspiration. From our brief excursion through history in Chapter One, we saw how the Greek ideals and their rationalism became fused with the Judeo-Christian values, and that from about the time of the Renaissance in the fourteenth century, two basically different types of humanism emerged and persist today. The first is theistic humanism, which holds to a belief in the centrality of God and is characterized by Catholic, including Anglican, thought. Within the spectrum of views held by theistic humanists, Charles F. Potter (1930) very clearly spelled out the destiny of this viewpoint in his Humanism, a New Religion.

The second is naturalistic or anthropocentric (man-centered) humanism nourished by the evolutionary thoughts of the nineteenth century and given its biggest impetus by Darwin. It is this second kind of humanism that constitutes secular humanism and is the predominant worldview today. It views mankind as an integral part of nature and thus denies the human soul; it limits values to what has value for humankind, and thus ethics and morals become situational; and it denies the existence of God or relegates him to a non-functional role. In short, secular humanism follows the famous dictum of Protagoras that man is the measure of all things and must create his own life. Natural man thereby replaces the supernatural God and becomes the master of his destiny (Holmes 1983, 16).

The atheistic base of secular humanism can be established precisely

from almost any of the humanist literature, but the statement in the preface

to the second Humanist Manifesto, published in 1973 (the first was published

in 1933), is fully representative:

As in 1933, humanists still believe that traditional theism, especially faith in a prayer-hearing God, assumed to love and care for persons, to hear and understand their prayers, and to be able to do something about them, is an unproved and outmoded faith. Salvationism, based on mere affirmation, still appears as harmful, diverting people with false hopes of heaven hereafter. Reasonable minds look to other means of survival (Kurtz and Wilson 1973, 4).

As one of today's leading spokesmen for humanism, Corliss Lamont

is more specific; he makes the following statement in his The Philosophy

of Humanism:

Humanism believes that Nature itself constitutes the sum total of reality, that matter-energy and not mind is the foundation stuff of the universe.... This non-reality of the supernatural means, on the human level, that men do not possess supernatural and immortal souls; and on the level of the universe as a whole, that our cosmos does not possess a supernatural and eternal God (Lamont 1977, 116).

Lamont also adds that "since agnostics are doubtful about the supernatural,

they tend to be Humanist in practice" (Lamont 1977, 45), precisely the

point brought out in the opening statements of Chapter Fourteen. The mere

rejection of God, however, does not necessarily produce a humanist since,

as it was shown in Chapter Thirteen, there is the counterpart religious

requirement of commitment. The commitment, in this case, is to a positive

belief in the possibilities of human progress. This belief is supported

by, and often results from, the belief in evolution, which is the essential

alternative to explaining our material existence, and Lamont dutifully

makes his confession of belief:

Biology has conclusively shown that man and all other forms of life were the result, not of a supernatural act of God, but of an infinitely long process of evolution probably stretching over at least two billion years.... With its increasing complexity, there came about an accompanying development and integration of animal behavior and control, culminating in the species man and in the phenomenon called mind. Mind, in short, appeared at the present apex of the evolutionary process and not at the beginning (Lamont 1977, 83).

One of the most marked characteristics of humanism is its amorality

as a result of a corrosion of traditional moral values. This may seem like

an evolutionary paradox; as implied earlier from the writings of Herbert

Spencer, in evolving from the animal, man passed from the amoral to the

moral. Spencer believed, as many still do, that ethics, as signified by

our legal code, has also evolved into increasing complexity. That being

so, we would expect traditional moral offenses to be legislated against

ever more severely. Such is not the case, however, because of two overriding

humanist mandates. The first argues that since there is no God, the Judeo-Christian

principles that form the basis of our legal system were not God given and,

consequently, can be changed to fit the situation without fear of divine

retribution. This is the root of today's teaching of situation ethics.

The second argument follows Rousseau's proposition that man is inherently

good and consequently reason dictates that it is simply the historic imposition

of harsh laws that has caused man to appear bad. Thus, freed from the metaphysical

fetters of Judeo-Christian principles, the humanist then believes that

man is free to be his own master. Lamont continues on the theme of man's

new found freedom:

For Humanism the central concern is always the happiness of man in this existence, not in some fanciful never-never land beyond the grave; a happiness worthwhile as an end in itself and not subordinate to or dependent on a Supreme Deity (Lamont 1977, 30).

Another humanist writer specifically links Darwin and humanist amorality:

Darwin's discovery of the principle of evolution sounded the death knell of religious and moral values. It removed the ground from under the feet of traditional religion (Chawla 1964).

Taken in their most elemental form, "religious and moral values",

whether they be for the Jew, the Christian, or the Moslem, are based on

the biblical ten commandments, the last six of which deal with man's relationship

to his fellow man. Many of these commandments apply to areas of man's sexuality.

It is, then, not surprising that the humanist movement has been vitally

concerned with "liberating" man from restrictive codes of sexual behavior.

We have seen that Margaret Mead supplied much support for this notion.

For example, the laws forbidding incest, which has been a universal taboo

since the days of Moses, have been relaxed in Sweden, thus permitting free

violation of the fifth commandment, while it is apparent that our media

are attempting to give every encouragement for violation of the seventh.

In the past few years, there has been a concerted effort on the part of

liberal educators to introduce sex education into the school system, while

more recently this has been accompanied by the availability of free and

confidential contraceptive services. The justification given is that these

services are necessary to combat venereal diseases -- particularly Herpes

simplex -- which have now gone beyond endemic proportions. This rationale

is actually a well-worn strategem. Yet, nevertheless, it still works, for

the public expectation is to equate authority with integrity. The strategy

consists of studied procrastination -- a House investigation committee

or a Royal Commission are the usual devices. Then, when memories are dim,

the early sequence of events is reversed so that the effect is now claimed

to be the cause. In this way, the heaping of more coals, rather than less,

on the fire is justified. Sex education was extended to even earlier school

grades.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) building in Paris. (Jones, UNESCO) |

The final humanist objective is socialist world government with, of

course, the humanist elite in control. To some, this may appear the rational

answer to the world's problems, yet a moment's thought on some of the horror

stories made public and that are associated with big government should

call to mind Lord Acton's warning in 1887: "Power tends to corrupt and

absolute power corrupts absolutely" (Acton 1972, 335). Nevertheless, the

humanist faith surpasses the historical record, and the humanist vision

includes full-scale nationalization of industry and dissolution of national

identity as each government becomes subordinate to the super-government.

The document that expresses this most clearly has only recently been made

public and consists of the framework policy for UNESCO, written about 1946

by Julian Huxley and mentioned earlier in this chapter. The UNESCO preparatory

commission "withheld sponsorship of the text" of this document, which meant,

in effect, that the policy of this public body was restricted to those

with a "need to know" for thirty years, by which time it was felt that

the climate of public opinion would accept its disclosure; it was finally

published by UNESCO in 1976 (J. Huxley 1976, 14). Having established that

the philosophy of UNESCO should be "evolutionary in background", Huxley

continues:

From the evolutionary point of view, the destiny of man may be summed up very simply: it is to realize the maximum progress in the minimum time. This is why the philosophy of UNESCO must have an evolutionary background and why the concept of progress cannot but occupy a central position in that philosophy (J. Huxley 1976, 23).

Shades of tautological reasoning may be detected in this statement

as it equates evolution with progress, but be that as it may, Huxley cautiously

introduces the idea of the one world government:

The moral for UNESCO is clear. The task laid upon it to promote peace and security can never be wholly realized through the means assigned to it -- education, science and culture. It must envision some form of world political unity, whether through a single world government or otherwise, as the only certain means for avoiding war (J. Huxley 1976, 23).

Finally, after proposing dissolution of national sovereignty, which

has since been attempted with the European Common Market, Huxley's policy

concludes:

The unifying of traditions into a single common pool of experience, awareness, and purpose is the necessary prerequisite for further major progress in human evolution. Accordingly, although political unification in some sort of world government will be required for the definitive attainment of this stage, unification in the things of the mind is not only necessary also but it can pave the way for other types of unification (J. Huxley 1976, 30).

The phrase "unification in the things of the mind" is perhaps one

of the key elements in the concept of single world government, and since

"maximum progress in minimum time" is a necessary mandate, unification

can most effectively take place in the nation's schoolrooms beginning at

the elementary grades where minds are most receptive. Skinner's work on

behavioral modification has been seen as a vital tool in unifying young

minds, and there are even serious advocates of modification by pharmacological

means (Ladd 1970).[28]

Unification of the Mind in the Schools

The humanist influence has been particularly forceful in the educational

field and, in recent years, has received an increasing and universal directive

from the UNESCO organization. As an early example of their intention to

abolish all ideas of national sovereignty, the following statement appeared

in the UNESCO publication entitled "In the classroom with children under

thirteen years of age"; it was intended for the teaching profession and,

although undated, was issued about 1949:

As long as the child breathes the poisoned air of nationalism, education in world-mindedness can produce only rather precarious results. As we have pointed out, it is frequently the family which infects the child with extreme nationalism. The school should therefore use the means described earlier to combat family attitudes (UNESCO 1949, 58).

In the United States the humanist element can be traced back as

far as Horace Mann, who proposed that removal of the Bible from the schools

would greatly increase genuine educational progress. Throughout the nineteenth

century, the Bible had been used, especially in elementary classes, as

a universally available book from which to teach good English and, at the

same time, to impart a code of moral behavior.

John Dewey (1859-1952) picked up Mann's banner and almost singlehandedly reformed the American school system to conform to humanist ideals; the Bible was banished and so, eventually, was school prayer. The present-day, somewhat questionable standards of the American educational system are thus seen by some to be directly attributable to Dewey. Dewey's humanist credentials were established by signing the first Humanist Manifesto in 1933, by contributing regularly to such left-wing periodicals as New Republic, and in receiving socialist honors for aiding Trotsky at his Moscow trial, in 1936-37. Dewey was responsible for introducing Darwin's theory into the American school system (Clark 1960).

The steadily increasing humanist influence on education eventually came into conflict with the Christian element at the famous Scopes "monkey" trial in 1926, described in Chapter Eight. The Christian cause was championed by William Jennings Bryan, who placed his faith in the common people and resented the attempt of a few thousand humanists "to establish an oligarchy over forty million American Christians" (Coletta 1969, 230) and dictate what should be taught in the schools. Bryan referred to it as a "scientific soviet" (Levine 1965, 289).

Today, the tables are completely turned, and the evolutionary interpretation

of natural science is taught in schools and universities to the exclusion

of any other interpretation. This has been brought about by the dedicated

efforts of liberal educators following in Dewey's footsteps and the virtual

absence of any opposition from the church. In the past decade, however,

mounting and effective opposition has been heard from a number of concerned

organizations spearheaded by the Institute for Creation Research, California

(Numbers 1982). The humanist influence on the American educational system

has been thoroughly documented by La Haye (1980) to whom parts of this

chapter are indebted.

Unification of the Mind by the Media

Finally, in completing this section on unifying the things of the mind,

we must recognize how our thoughts and opinions are molded by the information

we receive daily through magazines, newspapers, radio, and television.

For that reason there has traditionally been a system of checks and balances

whereby all facts that are known may be aired and opposing viewpoints heard.

For the past decade or so, however, mere lip service has been paid to this

vital freedom as news syndicates have coalesced to a single viewpoint --

that of the humanist.

In 1977 the Japanese celebrated one hundred years of scientific discovery with a National Exhibition and chose the Plesiosaur as discovery of the year for the celebration emblem. |

There has, in effect, been a censorship or severe curtailment of news items that do not support either the theory of evolution or the socialist ideals. An example of this type of censorship was the occasion of the catch of the dead creature by the Japanese fishermen in 1977 (described in Chapter Four). The discovery evidently came close to upsetting the foundation for secular humanism, and there was a virtual news blackout in the western hemisphere, even though the museums and the National Geographical Society were fully informed.[29] In contrast, the Japanese press, radio, and television gave this item full coverage and even commemorated the event with a postage stamp depicting the creature as a plesiosaur, or sea-dwelling dinosaur. Quite evidently, unfortunate incidents such as this discovery must come under full control. As a further step in accomplishing unification of the world's mind, the last item in the humanist manifesto is currently being put into effect. The item reads: "We must expand communication and transportation across frontiers.... The world must be open to diverse political, ideological, and moral viewpoints and evolve a worldwide system of television and radio for information and education" (Kurtz and Wilson 1973, 8). |

In 1980 the general conference of UNESCO in Belgrade adopted a resolution

to include the principles of a New World Information and Communication

Order. Since that time there has been a coercive attempt to bring the free-world's

television and radio news media under a single beneficent banner, purportedly

with the object of maintaining freedom of the press and information. However,

the United States government perceived the real motives to be quite the

reverse when it was suggested that journalists be licensed "for their protection",

and withdrew its membership from UNESCO in December 1983.

Who Are the Secular Humanists?

Not every believer in evolution is a humanist, but it is an essential

requirement that every humanist should believe in evolution. The distinction

is made by the humanist's having made a commitment to a positive belief