|

|

| << PREV |

|

|

False facts are highly injurious to the progress of

science, for they often endure long; but false

views, if supported by some evidence, do little

harm, for everyone takes a salutary pleasure in

proving their falseness: and when this is done,

one path towards error is closed and the road to

truth is often at the same time opened.

CHARLES DARWIN

(1871, 2:368)

The two previous chapters outlined the major features of man's search

among the fossils for evidence of his relationship to the higher animals,

yet there are biological features among living things which are claimed

as evidence for a continuous phylogenetic relationship, from the lowest

order of creature to man. Some of these features are the so-called vestigial

organs found, it is claimed, in both animals and man and believed to be

the remains of organs once useful in a prior evolutionary stage. Another

biological feature is the embryo, or fetal stage, of higher organisms including

man, which, it is said, reproduces in itself several earlier stages of

its long evolutionary history. Before taking a more detailed look at these

textbook favorites, however, this might be an appropriate place to say

something about heads, since the last two chapters were somewhat concerned

with this part of our anatomy. This subject will also serve as a foundation

for the final chapter.

Heads

It would be quite unusual these days to hear of an eminent man making a posthumous donation of his head to science. In the nineteenth century, however, this was quite a respectable thing to do. Many well-known writers, scientists, and notables in England and Europe willingly acceded to this service to science by allowing their heads to be removed as soon as decently possible after death, in order that the brain could be taken out, weighed, and studied. The idea that man's mind -- that is, the seat of his emotions, his intellect, and will -- is situated in the skull and, therefore, identified with the brain, does not have a long history and began in the seventeenth century with René Descartes. The first serious consideration was being given at this time to the study of man's soul, or psyche; since then the disciplines of psychology and psychiatry have been very much oriented towards the brain and considerable success has, in fact, been achieved in identifying, for example, various kinds of emotions with specific areas of the brain. In those early days, however, there was the unquestioned belief that every living person had a soul and that the soul left the body after physical death; attempts were made to prove this by weight-loss experiments after death, but without success. Although it is like looking in the stable for the horse after it has bolted, autopsy examination came up with the pineal gland, located in the front of the brain, as the seat of the soul, or the place where the soul had been during life. More will be said of the pineal gland later in this chapter.

Attention was then focused on the intellect as the more obvious manifestation

of the soul, and there were two observations -- both faulty. The first,

announced in 1859 by Paul Broca, professor of clinical surgery in the Faculty

of Medicine, University of Paris, stated that intelligence was directly

related to brain size and, consequently, to the size of the head. The facts

were then, as they still are today, that men of exceptional intelligence

tend to rise to prominent positions in society, and some of these individuals

do have larger than average heads. Jonathan Swift (1667-1745), author of

Gulliver's

Travels among many other writings, was one such well-known individual,

with a cranial capacity reckoned at an astonishing 2,000 cubic centimeters,

although this was never actually measured since he died before it became

fashionable to contribute exceptional heads to science. Cases such as Swift

nicely substantiated the theory, and later there were many others in which

weights of the actual brain were recorded rather than the volume of the

empty container, the latter being, of course, the only recourse in the

case of those long dead. For all practical purposes, in the case of brain

tissue, it makes no difference whether we speak of cubic centimeters or

grams: the units are interchangeable, and the figures can be directly compared.

The French paleontologist Georges Cuvier, with the most prodigious memory,

had a brain that weighed in at 1,830 grams, while Russian novelist Ivan

Turgenev's brain made the all-time record in excess of 2,000 grams. It

might be recalled that the average adult brain today is about 1,450 grams,

or approximately the same number of cubic centimeters.

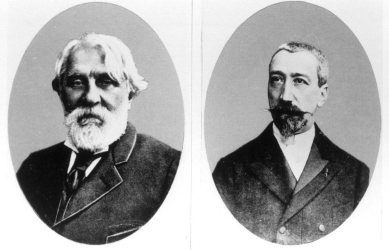

Ivan Turgenev, 1818-83 Anatole France, 1844-1924 2,000 grams 1,017 grams |

The cranial capacity of Homo sapiens, in

the range of 1,000-2,000 cubic centimeters (or grams), clearly bears no

relationship to intelligence.

(Turgenev: after the painting by Kharlamov c. 1880; France: photograph c. 1900; Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library Board) |

It was a great temptation for craniologists of the nineteenth century to select such facts as these to fit the theory, and, eventually, they became so self-convinced as to be totally blinded to those cases of ignorant men with larger than average heads. These men usually did not catch the attention of society, and it was easy to overlook or explain away this kind of data. However, what was not so easy to ignore or explain away were those cases of brilliant men with smaller than average heads. In 1855 the brain of the great German mathematician Karl Gauss (1777-1855) weighed in at a disappointing 1,492 grams; then, as their days expired, there were other brilliant men with smaller than average brains, and finally, in 1924, when the brain in the rather peculiar head of the French novelist and satirist Anatole France joined others pickled for perpetuity, it was found to be a mere 1,017 grams. Data of this kind could not be ignored, and the theory fell into disrepute, but it had been widely believed and promulgated for almost a century and still lurks in the collective unconscious today (Gould 1981b, 73).

The second great fallacy that arose from faulty observation was related to, and a direct outcome of, Lamarck's evolutionary thinking, which argued that the mechanism responsible for one species becoming another was that of the inheritance of acquired characteristics. The giraffe's long neck, acquired by generations of parents reaching for the higher leaves of trees, is the classic example. This notion was applied to man's brain -- the more he exercised it, the larger it became. The increase in size was said to be passed on to the next generation, which thereby had the immediate advantage over its normal neighbors by having a larger initial capacity for intellect. Darwin himself entertained Lamarckian reasoning, as we shall see in the next section, but the idea was not shown to be incorrect until the early 1900s, when the work of Gregor Mendel's genetics was understood and accepted. The Lamarck/Broca notion, that brain size increases with intellect and that this acquired increase is passed on to the next generation, is quite faulty reasoning, even though examples can always be found that appear to support the argument, and it has led to the most outrageous exercises in racial discrimination ever perpetrated in modern times (Haller 1971).[1 ] We will not pursue this fascinating horror story at this juncture but simply point out that these two related ideas were condemned to die in the Western Hemisphere shortly after the turn of this century. In Russia, Lamarckian thinking continued under Trofim Lysenko and was only abandoned in favor of Darwinian thinking with the death of Joseph Stalin, in 1953. However, in spite of all this well-known history, these ideas relating brain size to intelligence are still very much alive in the thinking of many today who really should know better but persist in perpetuating the myth (Tobias 1970).

The explanations put forward to account for one particular ape becoming man vacillate from the ape's purported ability to walk upright (bipedalism), to his discovered use of fire, to his ability to speak, and, most popularly, to the use of his brain. The use of the brain and consequent increase in size is the central preconception of those committed to find the elusive missing link. There has to be real dichotomy in thinking in order to be convinced that some extinct ape developed a larger brain, which enabled the creature to outwit and outsurvive others competing in the same arena of life. In making this claim, it has, at the same time, to be acknowledged that from all the work in the nineteenth century with living people and heads rather than fossils, the size of the brain, at least within the limits of 1,000-2,000 cubic centimeters, bears no relationship to intelligence. There can be no logical reason for claiming that brain size suddenly becomes significant in the range, for example, from 500-1,000 cubic centimeters, that is, from ape to man, except that this is a necessary a priori assumption in order to provide a framework for evidence to close that vital gap between ape and man.

This preconception can be seen to influence in a very tangible way the

practical matter of the reconstruction of fossil skulls, particularly when

the fossil is found in many pieces, some of which may be missing. If nature

had supplied us with a perfectly spherical head, it would be a simple matter

to determine the original skull size and, hence, the volume, from the curvature

of only one small piece. But, of course, heads are not like this but consist

of a multitude of curves, most of which would be known in only a general

way beforehand. Reconstruction is thereby a complex problem and very much

subject to the preconceptions of those doing the reconstruction. It may

perhaps be realized that a small difference in any gap left in the fitting

of the pieces to form a surface makes a large difference to the volume

of the finished reconstruction. If, for example, the fossil pieces were

discovered in strata believed to be half a million years old, the reconstructor

might expect to be dealing with a Pithecanthropine,

and the skull

volume, accordingly, would be greater than 750 cubic centimeters. Unconscious

bias, particularly in the hands of a skilled anatomist, would tend to fit

the pieces together tightly or loosely to finish up with the expected volume.

We saw that the reconstruction of the Piltdown skull gave volumes of 1,070

and 1,500 cubic centimeters in the hands of two experts with different

preconceptions. We may then ask what assurance there is of the validity

of Weidenreich's (1943) reconstruction of Peking man, which has exactly

the expected skull capacity, when all the original fossil pieces have so

conveniently disappeared.[2]

America's Golgotha

Even with complete skulls and accurate determinations of their volume,

other factors, such as the height of the individual, are directly related

and have to be taken into account. However, superimposed on all consideration

is the preconception of the investigator, since it is this factor alone

that has the greatest influence on the interpretation of the physical data.

The classic example of preconception is that of Samuel Morton, who had

more than a thousand complete and intact skulls to work with rather than

a few fragments. But first, a look at the social background of his times.

| In the early part of the nineteenth century when the Negro population of the southern United States was still in slavery, the white man became very divided on the question of racial superiority, which eventually led to the American Civil War in 1861. At that time the Bible was recognized as the standard by which to arbitrate all moral and ethical judgments, but those with a vested interest in the slave population found biblical arguments to support their own position. The ninth chapter of Genesis relates how the black races were descendants of Ham's son Canaan, who was cursed by Noah, and seems to indicate that they were forever destined to be the white man's servant. The South African policy of apartheid today began with this same biblical interpretation. A less popular school of argument (the polygenists) abandoned the Bible altogether and maintained that the races were separate biological species. Darwin cites one enthusiast who claimed that there were sixty-three species of man (Darwin 1871, 218). Even though interfertility between the races had been well demonstrated, attempts were made to expand the definition of "species" in order to accommodate the theory. |

Samuel George Morton, 1799-1851. Amassed one of the world's largest collections of human skulls and set the pattern for scientific racism for almost a century. (Library, Academy of Natural Science of Philadelphia) |

Whether arguing from biblical injunction or biological inferiority, the result was a no-win situation for the black slave. Moreover, whatever else was said, all were agreed that the Negro was of inferior intellect. And, of course, without educational opportunities for Negroes this reasoning was handsomely confirmed. The circularity of this argument was detected by some of the more enlightened, among whom was a fashionable Philadelphia physician of the polygenist school, Samuel Morton. Morton's single purpose of mind was dedicated to clear the air of this emotional issue and provide hard objective data showing the intelligence of Negro, white man and, for good measure, the North American Indian. Naturally, intelligence would be measured by skull capacity, and so it was that in the 1820s Samuel Morton began amassing one of the world's largest human skull collections, which may be found today in the department of physical anthropology at the museum of the University of Philadelphia. At great personal risk, friends of Morton dug up Indian graves and cemeteries, and contributed assorted heads. All were carefully identified as to racial origin. Morton personally measured the capacity of each, using lead shot, and proceeded to carry out an elementary statistical analysis on the results, which were eventually published in the beautifully illustrated volumes Crania Americana, in 1839, and Crania Aegyptiaca, for Egyptian skulls, in 1844. There was a summary volume in 1849.

Morton died an early death in 1851 and was regarded as a well-respected

scientist of his time who had provided the world with the definitive work

on racial intelligence. The figures confirmed what everyone "knew": the

white man was the most intelligent, the Indian next, and the Negro least

of all. In his most charitable and Christian way, the white man was seen

to be offering protection and security to his child-like black brother

by employing him as a slave -- wonderful justification, for no one could

refute the hard facts of science!

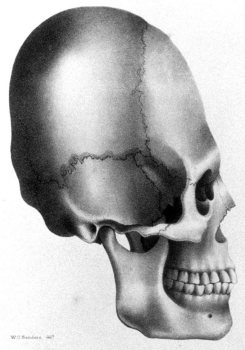

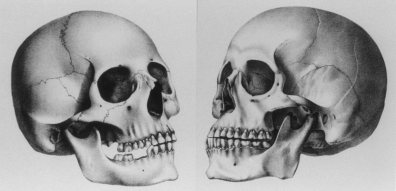

Skull of a Natchez Indian from Morton's collection. While it is recognized that odd-shaped skulls have been deliberately produced by "cradling" the head of the infant, there is nevertheless a wide variation in the shape of the human skull. Having a high or low forehead bears no relationship to intelligence. (Lithograph by John Collins; Academy of Medicine, Toronto) |

It wasn't until the late 1970s that Gould (1978) reanalyzed Morton's

original data and discovered that there was no statistical difference between

the white, red, or black population figures. In other words, there was

absolutely no basis for claiming that one race was any more intelligent

than another. The statistical reworking had clearly shown that, though

Morton was an honest man in that he had published his original data, he

was biased in his thinking and had unconsciously selected his data to fit

his three incorrect preconceptions: a) The Negro race was biologically

inferior to the white races; b) as a result of biological inferiority,

the Negro race was less intelligent; and c) intelligence could be measured

by brain size or skull capacity.

Fortunately, in spite of all the hard "evidence", slavery was abolished in North America in 1865, but we may never know just how much these efforts were retarded by Morton's definitive data. Morton's story has been included here as a classic example of prejudice that unconsciously influenced the interpretation of data, with the result that untrue and dangerous statements masqueraded under the impartial banner of science for more than a century. |

Vestigial Organs

Among the favorite pieces of "evidence for evolution", which is found in virtually every biology textbook, are what are claimed to be vestigial organs present in both plant, animal, and man. These are organs that are believed to have once been useful during a previous stage of evolutionary development but in continuing evolution are in the process of being selected out by modification. In other words, a changed habit or environment has rendered an organ redundant, and in disuse it has shrunk away until only a vestige remains. In chapter thirteen of the Origin, Darwin describes what he calls rudimentary, atrophied, or aborted organs, and he gives a number of examples from nature.[3] He includes the rudimentary pistil of some male flowers; rudimentary teeth in embryonic birds and whales; atrophied tails, ears, and eyes in certain animals; and atrophied wings in flightless insects and birds. He speaks of aborted organs, and notes certain features that are present in some varieties and absent in others of the same species -- for example, the absence of the oil gland in the fan tail pigeon (Darwin 1859, 22). Some years later when he wrote The Descent of Man, Darwin went on to list a number of human organs that he claimed were rudimentary and included the muscles of the ear, wisdom teeth, the appendix, the coccyx or "tailbone", body hair, and the semilunar fold in the corner of the eye (Darwin 1871, 1:19-31).

Having laid the groundwork principles, Darwin left it for others to explore the field in detail. In Germany the anatomist Robert Wiedersheim, a Darwinian enthusiast, fulfilling all the expectations of his country's reputation for thoroughness, produced a masterwork, in 1895, entitled The Structure of Man. In this work he listed eighty-six human organs that he claimed were mere vestiges, no longer having any useful function (Wiedersheim 1895, 200). In addition, he had a shorter list of organs, which he claimed were retrogressive -- that is, they were in the early stages of being atrophied. Wiedersheim's vestigial list included the pineal gland; the pituitary body; the lachrymal glands, which produce tears; the tonsils; the thymus; the thyroid; certain valves of the veins; bones in the third, fourth, and fifth toes; parts of the embryo; and certain counterparts of the reproductive structures of the opposite sex such as the clitoris. Of course, the list also included all those features mentioned by Darwin, such as the appendix and the coccyx.

Altogether this awesome list stood as landmark evidence of evolution in action, and, coming as it did from such a world authority in the field of comparative anatomy, it has been quoted and requoted in biology textbooks ever since. For example, the seventh edition of Villee's Biology claims there are more than one hundred vestigial human organs, but, in fact, the author mentions only six (Villee 1977, 773).[4] Other textbook authors, more conscious of the advances in medical knowledge during the past century, do not say how many vestigial organs there are but simply point to the appendix, or perhaps the coccyx, as examples.

At first sight Darwin's argument for vestigial organs as evidence for the theory of evolution may seem rational; the textbook authors claim it to be evidence, and this often causes the idea to be accepted without question. Darwin was very uncertain in his thinking as to why a vestigial organ should be evidence of evolution, yet, as usual, he comes away from his discourse fully convinced. However, a little thought and some insight show that the victory of his argument comes rather from the defeat of the case for Special Creation than from direct support for his own theory.

Nineteenth century writers of natural history advocated the idea of Creation and commented on the evidence of the Creator as the master Designer from design found in nature: each plant, animal, and man being perfectly designed for its particular environment. However, there were a few embarrassments, as there appeared to be some redundant organs, most noticeably, perhaps, nipples on the human male. Rather than cast doubts on the skill of the Designer, these apparent anomalies were explained as being created "for the sake of symmetry" or in order "to complete the scheme of nature". Darwin rightly pointed out that this was no explanation but merely a restatement of the fact (Darwin 1859, 453). On the other hand, his proposal that redundant organs were actually rudimentary, having been useful in a previous evolutionary stage, appealed to reason rather than sentimentality and was accepted by many. The critics, however, could see weaknesses in Darwin's explanation: for example, if the male nipples were a redundancy, this could only lead to the conclusion that in the past the young were fed at the male breast! (Darwin 1871, 1:31).[5] Nevertheless, for those seeking pure rationality, this detail was overshadowed by the redundancy claimed for all the other human organs and in doing so demolished the weak "symmetry" explanation used by the advocates of Creation.

The scientific aspects of the reasoning used to claim vestigial organs as evidence for evolution turn out to be rather hollow. To begin with, the notion is based on homologies: that is, all animals are claimed to possess some organs or structures that have no function, and these organs are homologous to organs that are functional in other related animals. The familiar example is the horse's ability to move its ears back and forth quickly, a very useful function for that animal. Man's ears are equipped with a similar set of muscles homologous to those of the horse, but of course, not nearly so well developed; the movement is thus much more limited. These muscles of the human ear were seen by Darwin and his followers to be vestigial, or mere rudiments of once fully functional muscles, capable of swirling the ears about when man was at a much earlier evolutionary stage (Darwin 1871, 1:19). To most biologists today, the presence of small organs, such as the human ear muscles, that seem to have no function in themselves but correspond to functional organs possessed by other animals, indicates inheritance from common ancestry.[6] Darwin (1871, 1:32) actually said this and it has been repeated, seemingly without the realization that the entire reasoning is Lamarckian (Darwin 1859, 457).[7] It will be recalled that Lamarck's mechanism for evolution of the species was by the inheritance of acquired characteristics. The long neck of the giraffe was acquired by the successive inheritance of slightly longer necks, produced by each generation stretching for the topmost leaves of the trees. The vestigial organ argument is exactly the same in principle, since it says that the rudimentary organs are acquired by successive inheritance of slightly smaller organs produced by disuse. Weismann's rather crude experiment, in which the tails of mice were cut off for nineteen successive generations (Weismann 1891, 1:444) convinced scientists at the turn of this century that Lamarck's ideas were invalid, and later when the inheritance of characteristics was found to depend on the DNA genetic coding and not habits, the reason why Lamarckism could not work was understood.

That Darwin's reasoning concerning vestigial organs is Lamarckian can be seen from two directions: from those examples that he and others claimed were vestigial and those cases that should have qualified as vestigial but were not so claimed. In the first place, Darwin's list of human organs, later expanded to more than one hundred by Wiedersheim, has now shrunk to two or three very questionable claims, due to advances made in medical knowledge, and leaves only one certainty, the male nipples, and, notably, most textbooks no longer include this item. Villee (1977, 773) makes an incredible exception! The medical advances made since Darwin's day have shown that virtually all of these vestigial organs do, in fact, have functions, many of which are very necessary at an early stage of our physical development. It would be a tedious exercise to list them all with their function, but a few familiar examples will help make the point that the former claims for functionless organs were made in ignorance, and it would be reasonable to say that any doubts that still remain will be dispelled as medical science advances. Scadding, writing in 1981, was forthright enough to admit that vestigial organs provide no evidence for evolution.

The thyroid gland. Once claimed to be useless, this is now known to be a vital gland for normal body growth, and oversupply or under-supply of this gland's hormone, thyroxine, will result in overactivity or underactivity of all body organs. Deficiency of this organ at birth causes a hideous deformity known as cretinism.

The pituitary gland. Another organ once claimed to be vestigial, this is now known to ensure proper growth of the skeleton and proper functioning of the thyroid, adrenal, and sex glands. Improper functioning of the pituitary gland can lead to Cushing's syndrome (gigantism).

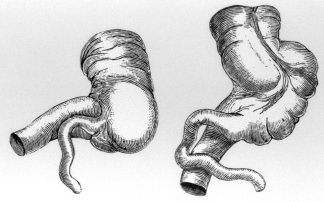

The tonsils and appendix. The thymus gland, the tonsils, and

the appendix are each a type of lymphatic tissue that helps to prevent

disease germs from entering the system and operates principally in the

first few months or years of human life (Maisel 1966). The human alimentary

canal can be regarded as a pipe extending from mouth to anus, while just

within the entry and exit ports are glands, the tonsils at one end and

the appendix at the other. These glands provide protection against invasion

of the body by pathogenic organisms. Once the child, during the first few

months of life, has built up sufficient resistance to the usual disease

germs, the importance of the appendix diminishes, while that of the tonsils

diminishes after the first few years. For this reason, should these organs

become infected, they can be removed from sufficiently mature patients

without apparent loss.

Man Ape The appendix in man and in the ape appear very similar and no doubt have the same function; some would see this as evidence for evolution, others recognize this simply as a common design. (Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto) |

The importance of these organs has been known among the medical

profession for more than half a century. For example, Sir Arthur Keith,

head of the Royal College of Surgeons, London, writing in the widely read

journal Nature,

in 1925, on the subject of imperfect organs, said,

"The tonsils, the thymus, lymphatic glands, and Payer's patches have similar

life histories, but no one would describe them as vestiges or rudiments"

(Keith 1925b, 867). In the same article Keith says of the appendix, "An

organ which increases in length until the twentieth year, or even until

the fiftieth, does not merit the name vestigial" (Keith 1925b, 867). Nevertheless,

writers of biology textbooks still regard the appendix as a vestigial organ

and as evidence of evolution.

Oddly, although the appendix appears in what are said to be man's closest relatives, the apes, it does not appear in his more remote relatives, the monkeys, but appears again, further down the evolutionary scale, in the rabbit, wombat, and opossum (Mivart 1873, 161). In light of these facts, the view that the human appendix is a vestige of an organ useful at an earlier evolutionary stage is difficult to explain (Gray and Goss 1973, 1242). |

The coccyx. Sometimes referred to as the "tailbone", this now is acknowledged to have the important function as a point of insertion for several muscles and ligaments, including the gluteus maximus, which is the big muscle that runs down the back of the thigh and allows us to walk upright. More will be said of the coccyx in the next section (Gray and Goss 1973, 118).

The semilunar fold of the eye. Some animals, and birds particularly, have a third eyelid known as the nictitating membrane, and it has been claimed, first by Darwin, that man has a vestige of this membrane at the inner corner of the eye. Contemporary books on anatomy describe this semilunar fold simply as that portion of the conjunctiva that aids in the cleansing and lubrication of the eyeball, making no reference to its being vestigial (Gray and Goss 1973, 1065).

The pineal gland. Once thought to be the seat of the soul and

later claimed to be a vestige of a third eye, presumably by some student

of Greek mythology, this gland is one of the remaining few for which the

function is still not entirely known. It is known, however, that tumors

of the pineal gland cause abnormal sexual functions, and in view of all

the other discoveries made, it would be foolish to claim that this organ

was functionless.

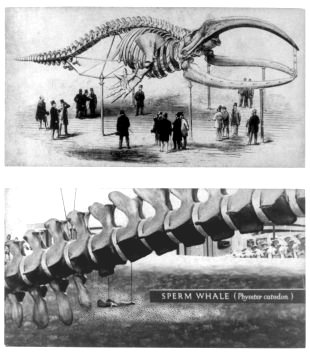

| UPPER: An early display of a whale skeleton at the British

Natural History Museum. Rather oversized vestigial "hind legs" can be seen

suspended near the tail.

LOWER: A photograph taken of the same exhibit gives a more truthful impression of the "legs". There is no sign of a pelvis or any attachment of these two small bones to the vertebrae. (Author) |

|

Returning to those organs that Darwin and others did not claim were vestigial yet which should have qualified according to the proposed definition, there are several interesting examples. The three-thousand-year-old Jewish practice of circumcision was mentioned previously but is still a valid example against the vestigial organ argument. Removal of the unwanted "organ" for more than one hundred generations has not made a fraction of an inch of difference, and Jewish male babies continue to be born "fully equipped". However, a more striking example was pointed out by Metchnikoff, a dedicated Darwinist, whom we shall meet later in this chapter. This enthusiast would have dispensed with half the organs of the human body, including the female hymen, which he carefully avoided calling vestigial or nascent but described simply as "useless and dangerous" (Metchnikoff 1907, 85); since it is absent in the anthropoid apes, he strangely considered it "new" to humanity (Metchnikoff 1907, 81). Metchnikoff said of the hymen that the only purpose it served was "the overthrow of the dogma of the inheritance-acquired characters" (Metchnikoff 1907, 85), and from this aspect it is fairly evident that, even though married three times, Lamarck was not overly familiar with this portion of the female anatomy.

Another example concerns the Chinese practice of binding the feet of girls. Having small feet was a mark of social distinction, and this practice was continued for several thousand years and only abandoned at the turn of this century. After generations of bound and virtually atrophied feet, the preferred small feet were never inherited, and Chinese babies continued to be born then, as they are today, with perfectly normal feet. The Flathead Indians of America provide another example; they bound or clamped the infant's head as quickly as possible after birth, while the skull bones were still supple, to produce the most peculiar-shaped heads. Presumably, this practice was of some importance to them, and a few examples may be found in Samuel Morton's classic Crania Americana (Morton 1839, plates 20 and 44) -- we can only imagine what odd-looking individuals these must have been in life. In any event, after hundreds of years of this practice, the Indian babies continued to be born with normal heads. The conclusion from all these observations is that neither mutilation, deformity, excessive development (of muscles), nor atrophy through disuse has ever been inherited over even a hundred generations.

With today's understanding of the role of DNA in the transmission of genetic characteristics, we would not expect these uses or abuses to have the slightest effect over any number of generations. The same reasoning would also apply to any of the vestigial organs claimed in the animal or plant kingdoms. Perhaps the most notable examples are the vestigial "hind legs" of the whale and the "hind legs" of the boa constrictor, but few authors claim these organs as vestiges today, since their function is now beginning to be understood (Carpenter et al. 1978).[8] Darwin recognized that variation within a species does occur, even to the point where an organ may entirely disappear. The absence of the oil gland in the fantail pigeon has been mentioned, but the creature still remains a pigeon; continued breeding will cause a reversion back to the common rock pigeon, complete with oil gland, so that it is evident that the genetic coding still retains this information in the fantail pigeon, even though it is not expressed. No one really expects the whale or the boa constrictor suddenly to "express" hind legs, although this is precisely the argument Darwin implied from his example of the pigeons.

To be as charitable as possible, it may be argued that Darwin simply had a theory about rudimentary organs that has since been shown to be incorrect, and that no harm has been done. He could be excused on the grounds of medical ignorance of his day, although there is no excuse for today's textbook authors (Biological Sciences Curriculum Study 1980).[9] It would not be true to say, however, that the theory has passed through history without causing harm. It has, in fact, been directly responsible for needless suffering at the hands of the medical profession for thousands who can only be described as victims of a delusion.

From the late nineteenth century, when the notion of man's emergence from the ape and the "evidence" of the vestigial organs began to appear in biology textbooks, medical students were required to subscribe to these ideas, and these students became the surgeons of the succeeding generation.

The French physician Frantz Glénard (1899) proposed the concept of visceroptosis -- a prolapse, or falling, of the intestines and other abdominal organs -- caused, he said, by man's erect posture. Very clearly this idea was based on man's supposed evolution from some lower animal. He wrote some thirty papers about this problem, and by 1900 the condition came to be called Glénard's disease. Patients complaining of abdominal pains, irregularity, and so on were advised to submit to ceco-colon fixation and/or gastropexy, each of which was a major operation intended to correct nature's fault by anchoring the colon and fixation of the stomach, respectively. Their original symptoms may or may not have been alleviated, but most of the victims were left with problems worse than those with which they began.

In England, Sir William Arbuthnot Lane was one of the most famous, skillful,

original, and indefatigable surgeons of his time. Because of his personality

and unusual powers of observation, it was said that he was the inspiration

for Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes. Lane had conceived the theory of autointoxication,

or self-poisoning, and claimed that, under certain circumstances, putrefaction

of the intestinal contents occurred; toxins were formed and absorbed, leading

to chronic poisoning of the body. By 1903 both the concepts of visceroptosis

and of autointoxication were combined and given support by the Russian

Nobel prizewinner Élie Metchnikoff (1907), who was a convinced evolutionist

and presumed that man's alimentary system, which served in an anthropoid

phase of human evolution, must be ill-adapted to deal with the dietary

requirements of civilized man (Metchnikoff 1907, 69ff ).[10]

Convinced by Metchnikoff, Lane at first performed a short-circuiting operation

(ileosigmoidostomy) to connect the lower end of the small intestine to

the far end of the large intestine.

Élie Metchnikoff, 1845-1916. Member of the prestigious Pasteur Institute, Paris. The famous scientist for whom the institute was named would have turned in his grave had he known what nonsense Metchnikoff was preaching in the name of science. (Author's collection) |

With further encouragement from the fearless Metchnikoff, who,

incidentally, was a zoologist and not a physician, Lane then performed

a colectomy, or removal of the entire colon. In his enthusiasm Lane believed

that this surgery was also of value in the treatment of duodenal ulcers,

bladder disease, rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis, schizophrenia, high

blood pressure, and a host of other ailments (Metchnikoff 1907, 248).[11]

Lane alone performed more than a thousand colectomies, while dozens of

other surgeons across Europe and the United States were stripping out the

colon vestiges and leaving untold numbers of victims, few of whom were

benefited more than temporarily. Many were made worse; some died (Layton

1956; Tanner 1946).[12]

The appendix was, of course, fair game in this drive to eradicate the troublesome vestiges, and it was not until the 1930s that these theories of visceroptosis and autointoxication began to be condemned in the medical textbooks, but the practices really only stopped with the demise of the practitioners and lingered on into the 1950s. The condemnation came about by the gathered evidence of such items as the wide diversity of bowel habits where, for example, it was discovered that it is not abnormal for some healthy individuals to go several weeks without a movement (Lambert 1978, 21). |

All this needless suffering, we are reminded, resulted from Darwin's

notion of vestigial organs, which he required as evidence for his theory

of evolution. This theory is still central to biological thinking, and

we may only surmise what other medical practices are being carried out

today based on this premise and also having little or no good effect.

Embryos

There are probably few readers who have never been exposed to the idea that during the first few months in the womb each of us, as an embryo, passes through various stages in which we have gills like fish and a tail like a monkey. We do not have to look very far to recall where we were first introduced to this impression: it was, of course, in the biology classroom where we met the Biogenetic Law, also known as the recapitulation theory, one that was presented as cardinal evidence for evolution. Ernst Haeckel's Biogenetic Law, postulated in 1866, is now discredited, but it has only been in very recent years that it quietly disappeared from biology textbooks, although it still finds its way into popular science books. Richard Leakey's Illustrated Origin of Species, published in 1979, contains Haeckel's nineteenth century diagram (Leakey 1971, 213), which, as we shall see, was shown to be fraudulent more than a century earlier. Interestingly, the diagram has been altered by a modern hand, while Leakey's text with the picture makes no reference to this but advances as truth what is acknowledged by science to be a discredited theory. Even the fifteenth edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica admits the discredited status, though obscurely, in the words, "The theory [of recapitulation] was influential and much popularized but has been of little significance in understanding either evolution or embryonic growth" (Encyclopaedia Britannica Micropedia 1974, 2:27).

Sir Gavin de Beer of the British Natural History Museum was more forthright. In 1958 he was quoted as saying, "Seldom has an assertion like that of Haeckel's 'theory of recapitulation', facile tidy, and plausible, widely accepted without critical examination, done so much harm to science" (Beer 1958, 159). Nevertheless, in 1958 and for almost two decades later, every biology textbook still presented the theory as factual, with the status of scientific law.

Just what was being said in the Biogenetic Law is important, because

a fraud was involved that deceived laymen and scientists alike for more

than a century; we should be aware that if it happened once, such a thing

may well have happened on other occasions. Several recent cases have, in

fact, been documented by Joyce (1981) and Ravetz (1971).

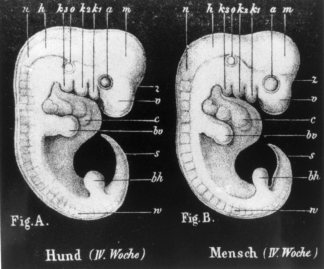

| Historically, naturalists before Darwin had observed that higher animals tend to repeat, or recapitulate, in their early development the adult stages of various lower animals. The resemblance of the tadpole of the frog to the fish is the classic example, and, in this case, the frog is regarded as being higher in the evolutionary scale than the fish -- shades of circularity can perhaps be detected in this reasoning. In the thirteenth chapter of his Origin, Darwin presented this notion as a principle by saying, "The community in the embryonic structure reveals community of descent" (Darwin 1859, 449). By this he was emphasizing the importance of the embryological evidence as support for his theory of the inheritance of slight modifications by descent. The widespread dissemination of this seed-thought in the Origin was bound to find some fertile ground, which, in fact, turned out to be the mind of Darwin's chief apostle, T.H. Huxley. Well aware that a good picture is worth a thousand words, Huxley included a pair of reasonably accurate drawings of the embryos of dog and man to show their similarities in his essay On the Relations of Man to the Lower Animals, in 1863 (in Huxley 1901, 7:77, fig. 3). Darwin used these same compelling drawings in his Descent of Man, in 1871 (Fig. 1). Haeckel, in Germany, seized upon Darwin's notion of recapitulation together with the idea of Huxley's illustration, and announced his Biogenetic Law, which he summed up in the dictum "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny" -- that is, the development of the individual repeats the development of his race (Gould 1977c).[13] Darwin had said nothing about man being included in the evolutionary order in the first edition of his Origin, but Haeckel had no scruples and published his ideas, in 1866, in a two-volume work entitled Generelle Morphologie der Organismen. By his own admission this was not a popular work because of his attempted scholarliness in trying to emulate the style of his idol, the poet Goethe. The idea and his own fraudulent illustrations were then presented in a more successful attempt two years later in his Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte (the English translation was published under the title, The History of Creation, Haeckel 1876).[14] Haeckel's energy and persuasiveness in promoting his ideas resulted in yet another volume, in 1874, generally referred to simply as Haeckel's Anthropogenie, which included a number of illustrations of various embryos. These pictures appeared in textbook after textbook for the next century;[15] they are the same pictures found in Richard Leakey's Illustrated Origin (textbook examples range from Romanes 1892 to Winchester 1971).[16] |

Ernst Haeckel's series of embryos showing three stages of development in the pig, the bull, the rabbit, and man. Initially, all the embryos look alike, but as growth proceeds they take on their individual forms. In Haeckel's view this is convincing evidence for evolution. In fact, the embryos show greater differences than appear in his diagram. (From Haeckel's Anthropogenie, 1874; Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto) |

Haeckel stated that the ova and embryos of different vertebrate animals and man are, at certain periods of their development, all perfectly alike, indicating their supposed common origin. Haeckel produced the well-known illustration showing embryos at several stages of development. In this he had to play fast and loose with the facts by altering several drawings in order to make them appear more alike and conform to the theory. Haeckel was a scientific draftsman of no mean talent and good optical equipment was available for his use. Yet the alterations were deliberate, because he began with accurate drawings that had been published several years before. Wilhelm His (1831-1904), a famous comparative embryologist and professor of anatomy at the University of Leipzig, pointed out the liberties Haeckel had taken with the illustrations to manufacture evidence for his law. In a catalogue of the errors, His (1874) showed that Haeckel had used two drawings of embryos, one taken from Bischoff (1845) and the other from Ecker (1851-59), and he had added 3-5 mm to the head of Bischoff's dog embryo, taken 2 mm off the head of Ecker's human embryo, reduced the size of the eye 5 mm, and doubled the length of the posterior. His concluded by saying that one who engages in such blatant fraud forfeits all respect, and he added that Haeckel had eliminated himself from the ranks of scientific research workers of any stature (His 1874, 163). His, whose work still stands as the foundation of our knowledge of embryological development, was not the first to point out the deficiencies of Haeckel's work, nor indeed was he the last, yet Haeckel's fraudulent drawings have continued to the present day to be reproduced throughout the biological literature. It is also notable that the exposure of Haeckel's fraud by His in 1874 has been confined to the German archives and nothing appeared in the English literature until 1997 -- over a century later! Michael Richardson and an international team of experts compared actual embryos, reported their work in the scientific press and showed conclusively that Haeckel's drawings misrepresent the truth (Pennisi 1997).

(Also see book: "

Haeckel's Frauds and Forgeries" 1915)

http://www.creationism.org/books/HaeckelsForgeries1915/index.htm

Haeckel's drawings made to show the resemblance of the dog and human embryos first appeared in the German edition of Natural History of Creation in 1868. They were exposed as fraudulent by Wilhelm His in 1874. (Author's collection) |

The alleged gill-slits in the human embryo become part of the face and are not connected in any way with our respiratory system. (Author) |

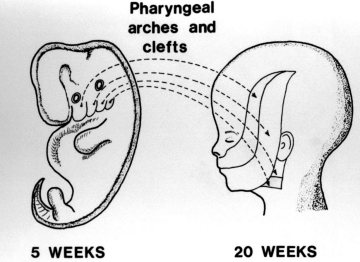

What then of the alleged gill slits and tail of the human embryo? In

the first few weeks of development, the human embryo does have a series

of creases having a superficial resemblance to those found in the fish

embryo; however, the creases have no respiratory function and later develop

into ear and jaw areas in the human, while those of the fish develop into

the gills. The notion of recapitulation only existed in the minds of those

such as Haeckel who wished to see this as evidence for the theory. The

analogy might be of two modern assembly lines for automobiles: at the early

stages both assembly lines appear very similar, but as development proceeds

it becomes evident that very different-looking cars are being built. In

no way could it be said that one car had evolved from the other, any more

than similarity of embryos is evidence of man's evolution from the fish.

A modern textbook on human embryology acknowledges the false impression

given in earlier texts in the following statement:

The pharyngeal arches and clefts [creases] are frequently referred to as branchial arches and branchial clefts in analogy with the lower vertebrates, [but] since the human embryo never has gills called 'branchia', the term pharyngeal arches and clefts has been adopted for this book. (Langman 1975, 262)

In the Descent of Man Darwin referred to the human os

coccyx or 'tailbone' as a tail, "though functionless" (Darwin 1871,

1:29). This became evidence for his theory, and from time to time ever

since, when an infant is born with a "tail", it has merited national press

coverage serving to keep the notion alive in the public consciousness.

This very thing occurred as recently as 1982 and began with a case reported

by Ledley in the respected The New England Journal of Medicine and

captioned "Evolution and the Human Tail"; the press, and ultimately the

public, could hardly fail to be convinced that some sort of evolutionary

throwback was being reported. Of course, the human coccyx was listed as

a vestigial organ for a century or so after Darwin, but in recent years

even this has finally disappeared from the pages of biology textbooks.

There are several facts, well known to the medical profession, that explain the myth of the human tail. In the first place, the adult human has thirty-three vertebrae, and the human embryo has the same number, never any more. This constitutes the "back bone" and "tailbone", but in the early embryo stage the assembly does look like a long tail since the limbs begin only as "buds". The anal opening is always at the end of the "tail" so that it takes its normal place in the anatomy upon full development. Very exceptionally, there is an anatomical defect in the coccyx of the newly born, and this has to be surgically corrected, just as the harelip has to be corrected, but the coccyx is never removed because it is a vestigial tail. Biology textbooks as recently as 1965 made the erroneous claim that individuals were sometimes born with a tail that had to be surgically removed, but all that has ever been removed is a caudal appendage. The caudal appendage occurs quite rarely, contains no bones, and has a fibrous fatty core that is covered with skin. It is not located at the end of the backbone but sticks out on one side. It has never been regarded as a "tail" by the medical profession, yet the author of the 1982 article, in describing what was a caudal appendage, clearly identified it with an evolutionary tail and thus perpetuated the myth.

Now that the Biogenetic Law, or recapitulation theory of the embryo,

has finally been discredited, it has been noted that biology texts, loathe

to give up what has served well as evidence for the theory for more than

a century, are now speaking about a "derived state" of the embryo. Toothlessness

in birds and in anteaters is given as the example of a derived state, but

a. moment's thought will show that this is nothing more than the vestigial

organ argument which, as we have previously seen, is based on the Lamarckian

mechanism and is known to be invalid. In other words, the fact that some

embryonic birds have teeth, whereas in the adult form they do not, does

not necessarily mean that the teeth are vestiges, but that they undoubtedly

do have some function just as the human appendix does at the fetal stage.

Why Erroneous Theories Persist After Being Discredited

Ever since the publication of Darwin's Origin in 1859, there has been a consistent trend, evident in these past five chapters, to interpret natural phenomena in a way that appears to provide evidence to support the theory of evolution. Some of these interpretations have turned out to be based on faulty observation, some on faulty reasoning, and some on blatant fraud, but the trend is always in the same direction. It might be asked why these unscientific illusions persist in spite of exposure within the scientific community, and why they have been maintained at the level of the general public, in some cases, for half a century. The underlying reason is not rooted in the plain facts of science but, rather, in unproved and unprovable philosophical beliefs and sociological views.

Darwin's theory of evolution has, in many minds, displaced the biblical Creation account of our origins, and to those who hold to this view it is vitally important to maintain whatever evidence there is, at least until sufficient better evidence can be found to replace it. To abandon discredited interpretations without replacement could place the theory of evolution in the perilous position of not being supported by any evidence whatsoever and incur the risk of having the creation account reintroduced. For this same reason, there is an extreme reluctance on the part of the scientific community to accept or even consider new evidence that does not support the current evolutionary dogma. Worse yet is the type of evidence that appears to give direct support to the book of Genesis, such as the fossilized human skull found in a coal bed and previously mentioned mentioned in the text and the footnote in Chapter 4, subsection, Age Names and the Geologic Column. Incidentally, this skull has recently been located in the Freiberg Coal Museum, East Germany.

Harding (1981) has concluded that the refusal to accept new information of this kind may be resolved into four attitudes:

1. The rationalistic model, which says that the only permissible approach is through reason and the established universal laws; no appeal can be made to the miraculous.

2. The power model. Though usually operating under a rationalistic model, this model is characterized by the scientist who dominates his field, seeking to maintain power, prestige, and pride of authorship. Often it is necessary to await retirement or even death of the individual before new ideas and better evidence can be introduced.

3. The indeterminancy model. Science has today become so specialized, with each discipline having its own technical language, that, unlike science in the nineteenth century, there is no spokesman knowledgeable in all fields. The communication of generalities from one specialty to another often results in unintentional overstatements and half-truths. Each specialist may question matters of evidence for evolution in his own field but remain confident in overall evolutionary theory, on the assumption that the other fields have all the really solid evidence.

4. The dogmatic model. This is characterized by an appeal to evolution as the "only scientific model for origins" and the statement that it is an "established scientific fact". That there are at least six mechanisms of evolution currently being proposed, with the experts divided among themselves, should alert the layman to the truth of the matter: nothing has been established.

The impression that scientists think rationally and fairly is a simplistic myth. The fact is they are subject to the same human failings as the rest of us. Looking inside the ivory towers we find the familiar power establishments, personality conflicts, and intellectual blind spots brought about by philosophical presuppositions. Several authors, such as Kuhn (1962) and Bereano (1969), have observed that science does not proceed in a smooth, orderly fashion but in fact remains virtually static under a dominant paradigm for long periods, before being overturned in a revolutionary manner. It may well be that science is on the brink of another revolution as voices within the ranks are raised against the theory of evolution. Rifkin (1983) has recently proclaimed this in print.[17] The only restraining influence would appear to be the united fear that, in the absence of anything else to replace it, some may be misguided enough to consider the creation alternative. In the next two chapters, we will see how the tricky subject of measuring time in the past has been handled by today's scientists, who, although competent, are still subject to the normal human failings.

|

|

| << PREV |

|