|

|

| << PREV |

|

|

Extinguished theologians lie about the cradle of

every science as the strangled snakes beside that

of

Hercules; and history records that whenever

science and orthodoxy have been fairly opposed,

the latter has been forced to retire from the lists,

bleeding and crushed if not annihilated; scotched,

if not slain.

T. H. HUXLEY

(1893, 52)

Whether we like to acknowledge it or not, man has a built-in propensity to worship some being greater than himself. Evidence from the most primitive tribes to the medieval cathedrals of Europe and the evangelical movement beginning in the 1960s and extending into the present day attest to this. Yet there will still be those who would question the relevancy of this activity for the twenty-first century. Part of the problem here is the word "worship", which, for some, has connotations of a candle-carrying, incense-swinging ritual, mindlessly played out to the strains of some Gregorian chant; for others, it is simply stoic attendance at an approved assembly. However, a moment's thought will show that the worship principle has a much broader application. The Fascist salute of the followers of General Franco or Adolf Hitler was a sign of adulation copied from the raised hands of the Jewish and Islam worshipper. The portrait banners of Joseph Stalin and Mao Tse-tung in principle were no less than the Roman Catholic banners and the Eastern Catholic icons. And May Day parades are held to glorify nature in the same way as the pageant and procession of religious festivals glorify God. Certainly, the "Alleluias" sung to the glory of God had their counterfeit in the paeans of "Seig Heil", sung by the Nazi party to the glory of their fuhrer, while the crucifix and swastika may be seen to fulfil similar purposes in the minds of their followers. The Madonna has been copied in the Atheist Church of America; the latter's Madonna, Madalyn Murray O'Hair was its founder. These are all forms of worship and are distinguished by who is being worshipped.

The parallel would not be complete without the books used in the same way as the Christian Bible for final authority and instruction. Familiar examples are the Book of Mormon, Hitler's Mein Kampf, and the little red book of Chairman Mao. Finally, the root meaning of the word "worship", which has to do with reverence, adulation, and the devotion shown towards a person or principle, can be applied alike to the names of Christ, Mohammed, the bishop of Rome, Karl Marx, or even Charles Darwin.

Most thinking individuals, at some point in their life, are faced with having to make a choice of the particular philosophical system they wish to follow. For example, one focal point for that choice lies in the vote cast for a political candidate. The belief in any one particular system eventually leads to a confession of that belief before others, which then has the effect of establishing a commitment to that belief system. This confession is an essential part of all religious systems but is also carried out by those organized activities that valiantly try not to be regarded as religious. The "harmless little ritual" imposed on the initiates of transcendental meditation, the oath taken by the competitors of the Olympic games, the endless affirmation of the cause by the members of the Communist party, and a similar principle of confession inherent in these activities, may be recognized in the continual and outspoken reference to the belief in evolution by informal discussion, at the oral examination, and from the lecture platform.

We have seen throughout the preceding chapters that there is no actual

proof for evolution; it has never been demonstrated by laboratory experiment,

and when all is said and done, it turns out to be a belief system (Keith

1925c).[1] Repeated

confession of belief in something for which there is no proof is a well-recognized

and practiced religious device, used to build the faith of the believer.

This applies whether that faith is in Special Creation, in evolution, or

in the existence of intelligent life in outer space. The principle is no

less true today than it was at the time of the Roman Empire. The emperor,

Marcus Aurelius, observed: "Such are thy habitual thoughts, such also will

be the character of thy mind; the soul is dyed by the thoughts" (Long 1869,

112).[2] It is well

known that certain books, when read and reread, have changed the lives

of individuals. Darwin was no exception. He confessed that the great merit

of Lyell's Principles was that it "altered the whole tone of one's

mind" (F. Darwin and Seward 1903, 2:117). More will be said of the religious

aspects of evolution in the following chapter.

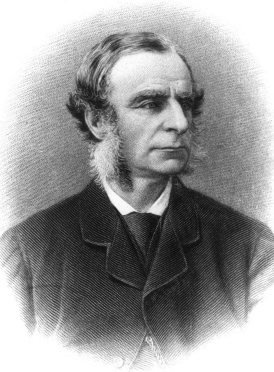

Issac Newton, 1642-1727. Although Newton is upheld as a British national hero, some of the seamier aspects of his life are not generally known among English-speaking people. (Engraving by W.T. Fry after the painting by Kneller; Academy of Medicine, Toronto) |

Another aspect of human nature, touched on in Chapter One, concerns

the individual's ability to accept the supernatural or the miraculous.

Taking an example from the Greeks, the Athenian people, in their long history,

had always been proud of their intellectual and artistic achievements;

they had, after all, produced some of the greatest philosophers, still

acknowledged to be so by the Western world today. Paul of Tarsus, a man

of no mean intellect, visited Athens almost two thousand years ago and

noted that the Athenians worshipped many different gods. He was invited

to tell them of the Christ, and they listened attentively until he mentioned

the resurrection from the dead, at which point they burst forth in mockery

and disbelief (Acts 17:31). All else up to this point had been perfectly

rational and natural, but now he was asking them to believe in the miraculous.

They felt their intelligence had been insulted.

The situation has not changed a bit since Paul's day, and many who, as did the Greeks, worship their particular gods find it difficult if not impossible to accept all the biblical miracles. For example, Westfall (1981) has pointed out that one of the greatest of English scientists, Isaac Newton (1642-1727), a deeply devout man, believing in Christ and the message of salvation, was racked with anxieties about the rationality of Christianity.[3] In fact, he actually committed himself to saving Christianity by rewriting the Bible and purging it of what he called the "corruptions", that is, the miraculous events (Cohen 1955, 72). He totally rejected the doctrine of the Trinity.[4] Newton's name is not alone, and a little digging into the writings of the famous reveals many who piously wrote of God's love and salvation but who, at heart, could not accept the miraculous. The Virgin birth and the Resurrection were too essential to the Christian creed to express open disbelief, but anything else, particularly events as remote as the Creation account and the Flood, eventually became fair game for skepticism. |

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, when evolution was

becoming respectable in some quarters, if not all, David Strauss (1846),

a German biblical critic, admitted that Darwin's theory was irresistible

to those who thirsted after "truth and freedom".[5]

In his The Old Faith and the New (1873), he expressed the feelings

of those not able to accept supernatural events, fairly typically as follows:

Vainly did we philosophers and critical theologians over and over again decree the extermination of miracles; our ineffectual sentence died away, because we could neither dispense with miraculous agency, nor point to any natural force able to supply it, where it had hitherto seemed most indispensable. Darwin had demonstrated this force, this process of nature; he has opened the door by which a happier coming race will cast out miracles, never to return. Everyone who knows what miracles imply will praise him, in consequence, as one of the greatest benefactors of the human race (Strauss 1873, 205).

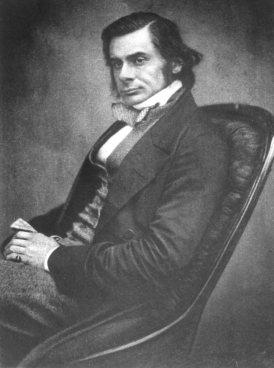

|

David Strauss, 1808-74. This German theologian openly expressed what many felt, that Darwin's naturalistic explanation had at last freed them from having to admit to the miraculous. (John P. Robarts Research Library, University of Toronto) |

The Roman Catholic and Protestant churches had always believed in a

supernatural dimension, while until the nineteenth century they had no

difficulty with the biblical miracles, including the six-day Creation and

the Genesis Flood. However, differences on the supernatural at the personal

level, in terms of revelation, were what initially divided Protestant from

Catholic. Beginning at about the time of the French Revolution, Christianity

itself was challenged from three directions. In the first place, the philosophers,

such as Descartes and Rousseau in France and later Hegel and Nietzsche

in Germany, cast doubt on the Judeo-Christian lifestyle and proposed alternate

worldviews. The second direction was from science, in the writings of Lyell

and Darwin, and the third from history, in the guise of biblical criticism.

This chapter and the next will attempt to show, very briefly, the church's

response to this challenge, and how the church leaders capitulated, so

that what some denounced from the pulpit as a damnable lie yesterday was

preached from the same pulpit as an eternal truth only a few years later.

Preparation for the Challenge

The great evangelical revival in Protestant England during the latter half of the 1700s, led by a handful of men such as John and Charles Wesley, was briefly introduced in Chapter Three. One outcome of this revival was an outspoken rejection of the ungodly philosophies that originated in socialist France and which were being emulated by a few English sympathizers. Perhaps one of the most influential naturalist writers of this period was the theologian William Paley (1743-1805), who published his Natural Theology in 1802. In his book he gave innumerable examples from nature of the evidence of design pointing to a Designer, and by this he hoped to combat the humanist influence of the pro-French philosopher in England, David Hume. Even so, Paley was not of the evangelical school and tended to leave God "out there" remote from his creation.

The evangelical revival spread to the colonies in North America and continued on through into Victoria's reign in the 1800s. The evangelicals were found mainly within the Anglican Church and in the then recently formed Methodist Church. The essential difference between the evangelical Christian and the conventional Christian, often sitting in the same pew, did not hinge on belief in the Genesis account of Creation and the Noahic Flood, since virtually everyone at that time accepted this as a literal fact. Rather, the distinguishing feature was the evangelical's active concern to bring others to an experiential and personal relationship with the Deity. This compelling inner drive was an outcome of the rediscovery of what had been found by the early Protestants in the Roman Church. It was based on the recognition that while man's five senses and reason (Aristotle's path to wisdom) were untrustworthy, it was possible to acquire a sixth sense and receive a higher wisdom through revelation. Only a minority, in terms of the overall Christian population, could accept this personal contact with the supernatural. But this minority was nevertheless highly influential (Howse 1976). Statistics may be questionable even when available, but one English example reports that in 1820 one Anglican clergyman in twenty was evangelical, and by 1830 the ratio had risen to one in eight (Hennell 1977, 513). By this time there had been a moral revolution in England: cock-fighting and bull- and bear-baiting had died out through lack of support; bookstores selling "dirty books" had closed down for lack of customers; and many of the Bible societies, missionary societies, and religious tract societies had been started. The Lord's Day Observance Society was founded in 1831. In government, many members were evangelical, while both houses of Parliament were extremely "right-wing", in comparison with any named governing party today. There is little doubt that this position had been reinforced by the memory of the awful consequences of the "left-wing" uprising in France. "Democracy" had become something not even to be contemplated (Howse 1976, 45).

This, then, was the climate into which Charles Lyell entered history,

in 1830, with his Principles of Geology. It was not well received

by the church nor by many others who were aware of it, even though Lyell

was cautious enough to present the case for uniformitarianism simply as

a possible explanation. However, most "men of the cloth" could detect this

as the thin edge of a very large wedge that would eventually undermine

the Christian faith, and they condemned Lyell's heresy soundly from every

pulpit. The more far-sighted may have recognized within it an unwitting

attempt to introduce socialism through science, but all saw it as a flagrant

violation of the Scriptures. In contrast to any individual today with unorthodox

scientific views, Lyell was in a sense insulated from criticism, since

he was independently wealthy and could take refuge in the company of like-minded

Fellows behind the doors of the Royal Society. Just at this time, during

the 1830s, when Lyell was struggling against evangelical orthodoxy, fate

provided the means by which some would be won over to the new faith. It

is a principle as old as Adam that the most effective way of introducing

a new belief system is first to prepare the minds of would-be converts

by creating doubt in the established creeds. This doubt came at precisely

the right time and from a direction not unfamiliar to the evangelicals

-- ancient Egypt.

Napoleon Bonaparte (Napoleon I), 1769-1821. Emperor of the French (1804-15) and megalomaniac, he adopted the Roman Caesar pose for this, one of many hundreds of portraits. (Engraving by C. Barth after the painting by Gerrard; Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library Board) |

The Long Shadow of the Sphinx

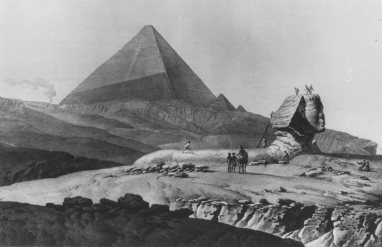

In the wake of the French Revolution, there arose one of the world's most infamous despots. Napoleon Bonaparte's quest to rule the world had brought him to Egypt, and by 1798 he had conquered the Mamaluke army in the Battle of the Pyramids. The evident signs of a once mighty civilization intrigued Napoleon, and he ordered a small army of engineers, artists, and scholars to record and describe the ruins (French Government 1809).[6] By the turn of the century, artists' engravings of imaginative reconstructions of the Pharonic palaces and temple began to appear in popular magazines and to excite the imagination of the public (Denon 1803; Roberts 1846-49).[7] The questions foremost in most minds would certainly have been, Who were these monument builders and how long ago did they live? Unfortunately, at that time no one could read the Egyptian hieroglyphics. But it seems fate had raised up a man whose specific task was to decipher the mysterious picture language.

|

Jean François Champollion, 1790-1832. A child prodigy, he seems to have been destined for the single purpose of breaking the secret of the Egyptian hieroglyphics. (Engraving after the painting by Leon Cogniet, 1831; Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library Board) |

The Greek portion of the Rosetta Stone recorded before the days of photography as a copper-plate engraving. (From the French government volumes Description de l'Egypt, 1825; Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto)

Jean François Champollion was born in France in 1790, under rather peculiar conditions (Ceram 1971a, 88).[8] It was said that while he was in his crippled mother's womb, she was miraculously healed by the local magician who prophesied that the boy-child she carried would achieve fame and be long remembered. Whatever the truth of the matter, it was evident by a very early age that he was a prodigy, and by the time he was sixteen, he had mastered half-a-dozen Oriental languages, as well as Latin and Greek; when he was seventeen he went to the University of Grenoble, not as a student but as a member of the faculty! |

In 1799 a hard black tablet, about three feet square, containing three blocks of text in three languages -- Greek, demotic Egyptian, and Egyptian hieroglyphic -- was discovered by Napoleon's army in the village of Rosetta. This memorial stone commemorated a victory that took place in 196 B.C. A plaster copy of the stone eventually became available to Champollion when he was in his prime, having mastered by this time a dozen ancient languages including Coptic, the oldest Egyptian language known.

He soon brought his lifetime knowledge of languages to bear on the task,

and by 1822 he had decoded the hieroglyphs. It seemed again that fate had

put him on earth for this one purpose, because he then spent the next ten

years preparing a grammar and dictionary of Egyptian hieroglyphics, and

with this complete he died at the age of forty-two; the great work was

published posthumously, between 1836 and 1841.

| With the key to Egyptian history before them, scholars now began to prepare king lists and work out dates for the various dynasties, and by the late 1830s several things became very clear. In the first place, the Egyptian civilization was far older than the Greek, which at that time was thought to be the oldest. Further, it appeared that there had been a continuous and highly developed civilization long before 2300 B.C., while, according to every theologian's interpretation of Genesis, this was about the time of Noah's Flood, which was believed to be worldwide. But this was not all. Since the earliest civilization was evidently so advanced in terms of the written language and the use of mathematics, it seemed only reasonable that there must have been a long unrecorded time prior to this when men were developing from barbarism to organized civilization. |

Napoleon's army expedition to Egypt explores the Sphinx and Pyramids of Giza. (Engraving from Description de l'Egypt, 1825; Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto) |

Worse was to come. Not once did the Egyptian records appear to mention the Israelites but according to the record in the book of Exodus, they had spent more than four centuries in Egypt and then made a most spectacular and memorable exit. This apparent absence of concordance with Jewish history cast doubt on Archbishop Ussher's chronology; for some in the higher echelons of the church, Lyell's interpretation of geology began to be viewed more favorably.

The new and popular science of archaeology in the nineteenth century

brought to light much evidence from the traditional Bible lands, some of

which appeared to refute, though much of it to confirm, the Scriptures.

The prejudices of the individual scholars translating and reporting these

discoveries have, however, always played a significant part in tipping

the scales of judgment in either one direction or the other. So far as

the apparent absence in Egyptian records of reference to the Israelite

nation is concerned, massive documentary evidence has, in recent years,

been put forward to show that traditional Egyptian dating should be advanced

by about six hundred years, which would then bring it into line with the

dating of surrounding nations, including Israel. The Papyrus Ipuwer and

the Tell El-Amarna tablets, discovered in Egypt, are cited as giving almost

line-by-line correspondence to details given in the books of Exodus and

Kings, respectively (Velikovsky 1952, 23, 223). More than four decades

ago when Libby was calibrating his carbon 14 method with wood from the

Pharaoh's tomb, he added a footnote from an eminent Egyptologist to say

that Egyptian historical dating was "perhaps 5 centuries too old" (Libby

1963, 278).[9

] To this

day the public is generally unaware of this albeit begrudged confirmation

of Egyptian and biblical concordance (Mure 1829).[10]

The entire issue still remains bogged down in controversy and while the

scholars try to forget Dr. Velikovsky, the sphinx, that symbol of ancient

Egypt, will no doubt continue to remain just as inscrutable as when it

was first seen by Napoleon in 1798.

Wavering Faith

Until the 1830s and the beginning of the controversy surrounding Lyell's geology, collecting fossils was a popular outdoor hobby in England as well as on the Continent; it was believed to be a tangible way of touching the Genesis record of the great Flood. However, the scathing execrations heaped on Lyell's Principles from almost every pulpit had, by association, given geology the reputation of a "dangerous science"; tampering with it would cause the faithful to "risk eternal damnation". Rock and fossil collecting began to lose its popular appeal and eventually a pall of gloom was cast over the whole exercise by the suicide of the author-geologist Hugh Miller, in 1856; more will be said of this later. The other popular pastimes of the nineteenth century included collecting beetles (the young Darwin was a particularly keen collector), collecting butterflies and ferns, and so on, but all with a sense of attaining a closer understanding of nature's master Designer. These activities were at first called natural theology. Later, what began as a hobby became for some a scientific profession, the word "theology" with its "religious" association was dropped, and the subject became known as natural philosophy; later, this was changed to natural history. Barber (1980) very attractively documents the relationship between the declining public interest in natural history and the coincident ascendancy of the theory of evolution.

Armed with what was believed to be unassailable Egyptian evidence for the mythological basis for the Bible, and with Lyell's interpretation of recent geological discoveries before them, a few leading lights of the church, who had always had difficulties with miracles, began to express their true feelings openly. They wrote their own interpretations in scholarly biblical commentaries. Impressed by their peers, some of the lesser lights began to waver in their faith.

At first, the authors of these commentaries felt compelled to reconcile

Scripture with geology and cautiously suggested that the great Flood was

merely a local affair. After a decade or so in print, this view was then

surrendered to that of the entire account of the Flood being a myth, or

at most, a spiritual analogy. The irony of this situation was that in the

nearly thirty years between Lyell's Principles of Geology and Darwin's

Origin,

the

most fruitful and practical work in geology was carried out by men such

as Adam Sedgwick, William Buckland, William Conybeare, Roderick Murchison,

Louis Agassiz, and others, most of whom in those early years were convinced

of the historicity and universality of the Noachian Flood.[11]

Nicholas Wiseman, 1802-65 |

Henry Manning, 1808-92 |

It has been mentioned previously that in any organization, such as a government department or a church denomination, the views of the man at the top -- the capstone -- are reflected, for the most part, all the way down through the organizational pyramid. When an underling disagrees with these views and says so, it is heresy; when those in highest authority change the prevailing view, it is held to be genuine enlightenment. The dates at which these moments of enlightenment came to be made can be pinpointed. For example, Dr. Samuel Turner, professor of biblical literature at the general theological seminary of the Episcopal Church in New York City (equivalent to the Anglican Church in Canada and Great Britain and an important seminary), published his Companion to the Book of Genesis in 1841. In it he claimed that the Flood was a local affair (Turner 1841, 216). Naturally, his students had to use this as a textbook, and so, within a few short years, this message was promulgated across a hundred American pulpits to a thousand parishioners. In England, one of the pillars of the Roman Catholic Church, Cardinal Nicholas Wiseman, in a series of twelve lectures published in 1836, rather more quickly abandoned the accounts of the Scriptures for that of geological science. The Roman Catholic Church in Germany began to cast off the biblical Flood under the teachings of Professor Reusch (1886) at Bonn University, in 1862. It is still possible to see how the commonly held belief in the Mosaic Flood was turned to unbelief in the nineteenth century by the cautious wording employed in the 1884 edition of Smith's Dictionary of the Bible. This book is popularly reprinted today, and the item in question will be found under "Noah" (Smith 1967).[12] A dreary catalogue of further examples is perhaps unnecessary to underscore the way by which a belief, held unquestionably true for several thousand years, first by the Jews and Arabs and then by the Judeo-Christian world, was abandoned little by little beginning with a few leaders of the Christian Church, though by no means all. One notable exception was Roman Catholic Cardinal Manning (1865-74).[13]

While the shades of disbelief in the Bible and the Flood in particular

were percolating downwards through the theological ranks, a series of archaeological

discoveries were made in the Middle East by the Englishman Austen Henry

Layard; his very exciting accounts were made popular during the 1850s.

Until this time the names of Nineveh and Babylon found so often in the

various books of the Bible had to be accepted on faith; there was in fact

not a trace of these allegedly huge cities. Layard (1849) was an extremely

capable and adventurous individual with a flair for languages and an ability

to write; his popular accounts are well worth reading, even today.[14]

He discovered the legendary city of Nineveh, excavated just a fraction

of the palace and the library, and shipped a great many priceless and massive

pieces back to the British Museum. A special department was built to house

those treasures that were proudly exhibited to an enthusiastic public.

Layard's friend, Emile Botta (1846-50), working for the Louvre museum in

Paris, had in the meantime discovered the fabled city of Babylon.

Reminiscent of Ezekiel's vision, statues of the strange creatures found in the palaces of Nineveh were removed by Layard and brought to the British Museum where they stand to this day. (From Layard 1849, Vol. 1; John P. Robarts Research Library, University of Toronto) |

The Bible accounts of these cities had thus been vindicated, and those of wavering faith could feel assured that the ground had not shifted beneath their feet (Brackman 1978).[15] The evangelical movement received a considerable boost because of Layard's discoveries (Bradley 1975; Habershon 1909; Thompson and Hutchinson 1929).[16] Later on, some of the Bible critics turned this biblical confirmation to their own advantage, as we shall see in the next chapter, but in the meantime, the reassurance that began with Layard in 1849 continued for the next decade. Then came Darwin in 1859. |

Loading the Dice

The ground had been prepared for Darwin over an entire generation in several ways and by no less than six editions of Lyell's Principles (Lyell made this boast to Haeckel; Lyell 1881, 2:436).[17] First, although Lyell never openly criticized the church or theological dogma of the day, his interpretation of the geological evidence that was then being gathered cast increasing doubt on the Bible's early chapters -- particularly on the account of the Genesis Flood. To some, the concept of an earth millions of years old rather than thousands began to seem more rational. Second, Lyell absorbed much of the invective heaped on his work by the church and the press, so that the blows later dealt against Darwin had by his time been considerably softened. Finally, all the controversy over Lyell's geology had actually been good publicity and served well to prepare the minds of would-be converts to Darwin's evolution. The stratagem of well-publicized controversy may be recognized as a pattern that has earmarks of deliberate orchestration and followed such events as the publication of the Origin, the Bishop Colenso affair in 1860, and the famous Scopes "monkey" trial of 1925 in Tennessee; more will be said of these events in the following chapters.

One other item of importance that paved the way for Darwin was the anonymous publication in 1844 of the book called Vestiges of Creation. Based on Lyell's principle of uniformity, the author described the development (evolution) from lower to higher forms of life over very long times; however, no mechanism for this development process was suggested. What was particularly shocking to the Victorian mind was that the deity was reduced to virtual redundancy by allowing nature to operate through the natural laws.

All the public outcry against the Vestiges had thoroughly condemned it, yet the book had planted an idea. Understandably, the author was not made known until forty years after publication, by which time its purpose had been served and even the dust of Darwin's controversy had mostly settled. The author was Robert Chambers, a distinguished Scottish author and editor (among his publications, Chambers' dictionary), who had actually secluded himself for two years to prepare for this work (Chambers 1844).[18] Since he knew that what he was saying would be controversial and had to be published anonymously to protect his reputation and business interests, what was his motivation? After all, there was no assurance the book would be a financial success. It happened that it was very successful, and ten editions were produced in as many years -- though, as every competent naturalist of the day knew, it was shot full of errors and flights of fancy. Darwin thought the book absurd but admitted "it had done excellent service ... in calling attention to the subject, in removing prejudice, and in thus preparing the ground for the reception of analogous views" (Darwin 1872, xvii).

There is evidence to indicate that a cadre of keen and influential minds

had been skillfully prepared to be apostles of the new faith for some time

before the publication of Darwin's Origin. The first edition of

the Origin was published in London on 24 November 1859, and contemporary

accounts give rise to the oft-repeated statement that an eager public bought

up the entire first issue of 1,250 copies on the first day. That the publisher,

John Murray, sold the entire issue is not in doubt, but the assertion that

it was bought by an eager public has been seriously questioned by Freeman

(1965, 21), since the book was not even advertised. What seems more probable

is that most, if not all, the first issue was bought up at the dealer's

auction by an agent of Lyell and Hooker a week or so before the official

date of publication. These copies were then sent gratis to known sympathizers

in positions of influence. This was not an uncommon practice, and two incidents

strongly suggest that this is precisely how Darwin's theory of evolution

was promoted.

| The first incident is documented in the biography of Philip Gosse

(1907), an experienced naturalist and member of the Royal Society who was

also in the 1850s a very popular writer of natural history. The biography

states that he was approached by Joseph Hooker, after one of the Royal

Society meetings during the summer of 1857, as a possible candidate for

enlightenment into the mysteries of natural selection. Evidently, it was

Lyell's idea to quietly sound out and initiate a core of influential naturalists

sympathetic to the idea of the mutability of the species -- those, that

is, who found difficulty with the supernatural creation and fixity of the

species (Gosse 1907, 116).[19]

Gosse's biography shows that, after he was approached on this very issue by Hooker, Darwin then made the same overture, all of which took place more than two years before the Origin was published. As it happened, Gosse was a member of the Plymouth Brethren and a firm believer in the biblical fixity of species; he would have nothing to do with the heresy being hatched by Lyell and company. It is highly unlikely that Gosse was the recipient of one of the copies of the first issue of the Origin, since he had by this time made clear his views on the subject of origins in his Omphalos, a rather strange and totally unsuccessful attempt to reconcile geology with Genesis (Gosse 1907, 121).[20] |

Philip Gosse, 1810-88. Experienced naturalist, author, and member of the Plymouth Brethren Church, he would not abandon the biblical fixity of species. (Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto) |

The second incident is found in the correspondence of amateur naturalist,

author, and Anglican divine, Charles Kingsley. Kingsley had been approached,

found to be, as suspected, a sympathizer, and did receive a copy of the

Origin.

Interestingly,

Kingsley's letter of thanks to Darwin was dated 18 November 1859; he must

have received it a full week before the official publication date (F. Darwin

1887, 2:287). Kingsley wrote, "I must give up much that I have believed

and written." To underscore the victory, Darwin quotes from Kingsley's

acknowledgment in the second edition of the Origin:

A celebrated author and divine has written to me that "he has gradually learnt to see that it is just as noble a conception of the Deity to believe that He created a few original forms capable of self development into other needful forms [evolution of one species from another], as to believe that He required a fresh act of creation to supply the voids caused by the actions of His laws" (Darwin 1860, 481).

Charles Kingsley, 1819-75. Seduced from the orthodox faith by Charles Darwin, he quickly adopted the new faith and was rewarded for doing so by being made Canon of Westminster in 1873. (Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library Board) |

Darwin had lost no time in quoting from Kingsley, since the second

edition appeared only two months after the first (January 1860), while

there is little doubt that this confession from a notable member of the

clergy was extremely helpful in overcoming the major source of opposition

to the theory.

Kingsley's expression "self development into other needful forms" soon found its outworkings in his book for small children written about two years later, in 1863, while on a fishing holiday. Entitled The Water Babies, this work is fairly typical of Victorian literature of its genre. Whereas most paid respect to Father God from evidence of design, however, Kingsley modified this to Mother Nature, with allusions to evolution (F. Kingsley 1904, 245).[21] The story has the child, Tom, approach Mother Carey (a synonym for Mother Nature), expecting to find her "making new beasts out of old". She explains to him that she has no need to go to that much trouble but simply has to sit and "make them make themselves" (C. Kingsley 1979, 232). It is a remarkable fact, when the outdated Victorian moralizing is considered as well as the quite dreadful illustrations, that Kingsley's little book is still in print; a reprinted edition appeared as recently as 1979. |

Charles Kingsley may be taken as typical of many men of the clergy,

not only of his own time but perhaps especially those today who feel somehow

intimidated by the men of science. After he made his confession of belief

to Darwin and shortly after the publication of The Water Babies, he

was elected a Fellow of the Geological Society in 1863; he had been promoted

by Lyell. Kingsley wrote in gratitude for belonging to the society: "I

feel how little I know and how unworthy I am to mix with the really great

men who belong to it" (F. Kingsley 1904, 249). Did he but know that some

of the most cherished ideas of Darwin were shown to be "vacuous tautologies"

by men of science almost a century later, he almost certainly would have

turned in his grave, which is, incidentally, near Darwin's in Westminster

Abbey.

|

|

Turning Point

The actual moment of truth in the confrontation between revelation and reason, between the mind-set of four millenia and Darwin's evolution, came on 30 June 1860 at the Oxford meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. The first edition of the Origin had been judiciously placed in sympathetic hands high in church and state. The second edition had been assured of public success by good fortune appointing Thomas Huxley to write the influential London Times (26 December 1859) book review of the previous month, and now all was ready for the contenders to enter the lists.

As usual Darwin was ill at the time and did not attend the Oxford meeting, but Huxley had arisen as a self-appointed bulldog, who was to prove to be Darwin's most able mouthpiece. The motivating force that drove Huxley was his feeling of animosity towards the clergy who. at that time, had far greater status than the scientist. Huxley found the hard facts of science to be an invincible weapon to use against the pompous rhetoric of some of the authority figures in the Church of England. Years later, as he looked back over the battle for Darwinism, he said, "My dear young man ... you are not old enough to remember when men like Lyell and Murchison were not considered fit to lick the dust off the boots of a curate. I should like to get my heel into their mouths and scr-r-unch it round" (Ernie 1923). Although he did not agree with all that Darwin had said, the Origin gave him the opportunity he needed to do public battle with church authority.

The opposing contender and champion of the orthodox view was Anglican bishop Samuel Wilberforce, son of the famous politician William Wilberforce and well known for his debating skills. Although a theologian, Wilberforce was an extremely able naturalist and no ignoramus to science; he had acquired a first in mathematics in his graduate days at Oxford. The popular accounts of the debate invariably depict Wilberforce as the unreasoning bastion of prejudice who finished as a broken pillar of the church, but Lucas (1979) shows that the facts do not support this view.[22] In the first place, it may confidently be said that not one of the dozens of different accounts is correct, because there was no shorthand record of this famous debate, so that all that has been written is based on hearsay. Secondly, Hooker was there (Lyell was absent) but neither thought that the bishop had done badly, but said that it was rather Hooker himself who had made the case for Darwinism.[23] Finally, Wilberforce had written a review of the Origin shortly before the debate of 30 June 1860, and it was published the following month; it would seem likely, therefore, that his presentation would be based on this review. The review contained very carefully argued points showing that in view of the known stability of species, Darwin had not made out his case in supposing that one species could be transmuted into another (Wilberforce 1860). Darwin acknowledged the cogency of this critical review article as "uncommonly clever: it picks out with skill all the most conjectural parts, and brings forward well the difficulties" (F. Darwin 1887, 2:324).[24]

The outcome of the Oxford debate was that Darwin and evolution were

perceived to be the victors, while Wilberforce and the church retired to

nurse their battered status, to retrench and perhaps find some compromise

to restore the Bible's tarnished image. This was very largely true, although

there was an intense but diminishing rearguard battle as, one by one, theologians

capitulated to accept what was really at this time still only a minority

view among scientists.

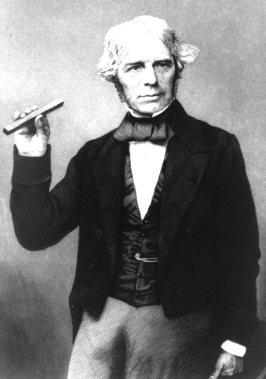

| There is a tendency for accounts of nineteenth century science to focus on Darwin and neglect to mention such men as Michael Faraday, James Maxwell, and William Thomson, later Lord Kelvin, who at the time the Origin was introduced were the true giants of science. These men had great credibility among scientists of the day and never did accept Darwin's theory; neither were they hesitant to defend the biblical account of origins. Within a decade of the publication of the Origin, however, so many of the church leaders had found some sort of compromise between the Darwinian and scriptural versions of man's origins, there was little opposition -- at least little that could be expressed openly in the national press. As each newspaper, magazine, and journal became committed to the evolutionary position, it grew increasingly difficult to publish articles with the opposite viewpoint. Consequently, those of the clergy who still objected to Darwin often found the press closed, and they had to resort to the use of tracts. The general argument of those who still defended the biblical position of origins was that once a part of the Scriptures was discredited and relegated to myth and legend, it would then be easy to discard any other part that happened to be difficult to believe -- the Virgin birth and the Resurrection were seen as eventual candidates. They further pointed out that central to the Christian faith was the belief that Jesus Christ was the Son of God and that he acknowledged the writings of Moses and specifically mentioned Abel, the son of Adam, and the Flood of Noah.[25] If these accounts were not literally true, they argued, then Christ was either completely ignorant and not the Creator he claimed to be, or he was a liar; either way, there could never be certainty that anything else he said was true (Bozarth 1978).[26] This line of reasoning had been voiced since the controversy over Lyell's Principles, but now it was beginning to divide between liberal and conservative views within the church. As a result, various compromise solutions, some quite ingenious, were proposed. |

Michael Faraday, 1791-1867. One of the true scientists of the nineteenth century whose electrical discoveries have benefited mankind. He never accepted Darwin's theory. (Engraving by Johnson Fry of Faraday holding a bar magnet; Academy of Medicine, Toronto) |

Compromises -- Day Age and Gap Theories

Nineteenth century people were avid readers and familiar with the controversy surrounding Lyell's geology. As new discoveries were made, particularly those that appeared to contradict the Genesis account of Creation and the Flood, there arose a need for some sort of reconciliation whereby both science and Scripture could be true. Unlike much of common thought today, most people of that era believed that the Bible was divinely inspired and without error. The multiple catastrophe-recreation theory of Cuvier (described in Chapter Three) had been a popular compromise in England for a short while but virtually collapsed in the face of Lyell's evidence of apparently so many catastrophes. More than that, however, reconciliation seemed impossible when geology demanded millions of years and Genesis would only allow a few thousand. Then an ingenious Scot appeared on the scene to popularize a solution.

Hugh Miller had been brought up with a Calvinist background and believed

in the literal interpretation of the book of Genesis. An unusual man, he

worked as a stonemason in the quarries, which gave him an intimate familiarity

with the rocks and fossils, while at the same time he was highly literate,

with a rare gift for writing. He wrote several books glorifying the rocks

and their maker and in this way helped to dispel much of the negative aspects

of Lyell's geology.

Hugh Miller, 1802-56. Stonemason, geologist, and author, this talented Scotsman shot himself in a fit of depression on Christmas Eve 1856. (Author's collection) |

The working classes could easily identify with Miller, which made his books extremely popular. He was much opposed to the implications of Lyell's geology and, particularly, to Chambers' Vestiges. In arguing against progressive development (evolution), he pointed out that geology revealed a regression of life as often as a progression. Working at the rock face for many years, Miller was certainly in a better position to make this statement than Lyell or the author of the Vestiges. Miller (1849) wrote Footprints of the Creator to refute the Vestiges, which had appeared five years earlier. However, with his Calvinist doctrine of innate immortality he became very muddled in his arguments against Darwinian progression and the destiny of animal and human souls. Nevertheless, he did conclude, "though the development theory be not atheistic, it is at least tantamount to atheism. For, if a man be a dying creature, restricted in his essence to the present scene of things, what does it really matter to him, for any one moral purpose, whether there be a God or no?" (Miller 1849, 14; later editions, 39). This statement, made in 1849, echoed the sentiments of many of the clergy throughout the rest of the century, while its prophetic outworkings are painfully evident in our society today. |

During the extensive geological work that accompanied the Lyell controversy, many new fossil species were found; the ark of Noah was becoming impossibly crowded, and Miller adopted and popularized the view then being considered by others, including Lyell, that the Flood was not universal but simply a local event. This was really a serious departure from the orthodox belief. Some, however, accepted it as a compromise, seemingly without considering that a local flood made it unnecessary to build an ark at all since Noah could simply have moved out of the area. The local flood idea had other problems, because at that time the fossils in the sedimentary rocks were held to be the result of the Genesis Flood, and sedimentary rocks were found throughout the world. This strained interpretation of the Genesis account was caused by the great number of species being claimed at that time by the naturalists, but, as it was pointed out in Chapter Six, some scholars are beginning to realize there may have been archetypes, which would reduce the overall number considerably.

Miller (1857) made one other important concession and interpreted the Mosaic "days" of Creation as epochs, with the final three days corresponding to the primary, secondary, and tertiary geological periods. Miller claimed that the days were twenty-four hours, but that they took place on top of Mount Sinai as a revelatory vision of Creation given to Moses and were not at Creation week (Miller 1857, 179). Others of his time had applied a similar sort of argument based on the biblical dictum, "One day is with the Lord as a thousand years, and a thousand years as one day." Thus, the Creation week could in this view be six thousand years (2 Peter 3:8). Miller and other geologists "knew" that six thousand years was a hopelessly inadequate time for sedimentary deposits to build up hundreds of feet deep; for this, millions of years were needed. However, the Scripture clearly said "thousand" and not "million", so this became another strained interpretation, generally referred to now as the Day-Age theory. Two very similar theories are popular in some circles today and are known as "progressive creationism" and "concordism". In deference to radiometric dating, both of these theories equate the days of Creation week with lengthy periods of geological time and are essentially Day-Age theories (Ramm 1954).[27]

Miller's version of the Day-Age theory was popularized in his Testimony

of the Rocks, which was actually published posthumously, in 1857, since

he shot himself in a fit of depression on Christmas Eve 1856. Those of

the clergy still loyal to the literal interpretation lost no time in pointing

to Miller's suicide as a consequence of bending Scripture to fit science,

and so not only the credibility of his argument but geology as a hobby

then quickly lost popular appeal.

| An earlier attempt to reconcile geology and Scripture had been put forward by another Scotsman, Thomas Chalmers, an evangelical professor of divinity at Edinburgh University. He founded the Free Church of Scotland, and because of his outreach to the poor and destitute he later became known as the "father of modern sociology". Traceable back to the rather obscure writings of the Dutchman Episcopius (1583-1643), Chalmers formed an idea, which became very popular and is first recorded from one of his lectures of 1814: "The detailed history of Creation in the first chapter of Genesis begins at the middle of the second verse" (Chalmers 1857, 5:146). Chalmers went on to explain that the first statement, "In the beginning God created the Heavens and the Earth and the Earth was without form and void and darkness was on the face of the deep," referred to a pre-Adamic age, about which Scriptures was essentially silent. Some great catastrophe had taken place, which left the earth "without form and void" or ruined, in which state it remained for as many years as the geologist required. Finally, approximately six thousand years ago, the Genesis account continues, "The Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters." The remaining verses were then said to be the account of how this present age was restored and all living forms, including man, created. |

Thomas Chalmers, 1780-1847. The engraving shows the subject at forty-one, just a few years after reintroducing the idea of a gap of indeterminate length between Genesis 1:1 and 1:2. (Knox College Library, University of Toronto) |

This explanation, variously known as the Ruin-Restoration theory, or simply the Gap theory, allowed that all the fossils were evidence of the life that once existed in the pre-Adamic age, while it still permitted the Genesis "days" to be literal twenty-four-hour days. The theory was attractive and seemingly offered the perfect reconciliation between science and Scripture -- provided neither was examined too closely. It was adopted, perhaps uncritically, by a number of writers in the nineteenth century, but notably by Pember, with his Earth's Earliest Ages and Their Connection With Modern Spiritism and Theosophy. This was first published in 1884 and continued under a slightly different title on to the fifteenth edition, in 1942 (Pember 1884).[28] The theory eventually became canonized into the faith by being adopted into the footnotes to the popular Scofield reference Bible. First published in 1909 and republished regularly since then, the theory may be found in recent editions as the footnote to Isaiah 45. However, by no means did everyone subscribe to the Gap theory, since it involved so much special pleading for the interpretation of certain Hebrew words and because it could not be reconciled with several other important statements in Scripture. For example, one of the important doctrines stated in Scripture is that death, as evidenced by the fossils, came after Adam and not before (Romans 5:12).

Today, in the light of serious deficiencies now evident in Lyell's uniformitarian geology, very few who favor any sort of biblical view hold to the Gap theory (Custance 1970; Fields 1976).[29] Rather, they have found it more believable simply to accept the literal understanding of the first chapters of Genesis, without the complications of "gaps" or "days" meant to be "ages". Those who hold to this literal view of fiat creation, often referred to as "Creationists", are now a fast-growing minority and represent a full-circle return to the belief in the total inerrancy of the Bible, which was the common position before Darwin (Numbers 1982).[30]

These, then, were some of the more popular attempts to reconcile geology

with Genesis, and many of these ideas still linger in the collective unconscious

today. Each of these attempts mixes more or less science with more or less

Scripture and produces a result more or less absurd. But many now believe

there is a more elegant way of reconciliation and thus present Christianity

more respectably before the altar of science. Basically the argument states

that God used the method of evolution to bring all things into being. The

next chapter will examine the origins of this popular notion in both the

Protestant and Catholic churches and set the scene for the final chapter

where science, church, and politics each gravitate to become universal.

|

|

| << PREV |

|