|

by Luther Sunderland · ©1988 · PREV NEXT |

|

by Luther Sunderland · ©1988 · PREV NEXT |

The Fossil Record Reptile to Man

Reptile to Bird

Many evolutionists believe that the most impressive evidence of an evolutionary transition is that indicating the conversion of a reptile into a bird. When the author participated in the production of six television programs at the British Royal Academy in London in June 1982 to commemorate the centennial of Charles Darwin's death, the fossil bird Archaeopteryx was offered by the evolutionist experts as one of the best evidences of common-ancestry evolution. (Two others were the peppered moths of England and Darwin's finches). Let us examine the fossil evidence for this assumed transition in considerable detail to try to determine if it is as compelling as evolutionists contend.

The author questioned Dr. Eldredge about the supposed conversion of scales into feathers since all birds (class Aves) have feathers and all reptiles have scales. He said that feathers were a neat evolutionary novelty and that the only things you have to work on are inventions. It is like tracing the history of manuscripts. Somebody makes a mistake in copying manuscripts and then the mistake is perpetuated. He said that this gives you insight into the historical lineage of that manuscript and the same thing is true with evolutionary inventions. He continued, "If you invent feathers, the supposition would be (which could be falsified) you'd see feathers and see the distribution of feathers and you'd guess that all of the things that have feathers are related." He admitted that this supposition could be wrong. Of course his comparing the supposed invention of feathers to typographical errors in manuscripts has no bearing on whether there was any actual evidence that feathers evolved from scales.

According to Dr. Eldredge the fossil bird Archaeopteryx shown in Figure 3 had some of the "advanced characteristics of birds and retained a tremendous amount of 'primitive' characteristics, like teeth.

He was asked, "Isn't that true of every subclass of vertebrates, some

have teeth and some do not, so how could that show reptilian ancestry?

Some fish have teeth and some don't; some amphibians have teeth and some

don't. Other ancient birds had teeth, and some mammals have teeth and some

don't. How could you classify teeth as reptilian?" He replied that he did

not say they were reptilian, but that the teeth were primitive.

|

Then he was asked, "How about man; does the presence of teeth show

him as primitive?" And he replied, "Sure." It was pointed out that children

have been taught in school that Archaeopteryx was transitional because

it had teeth and we do not want to put that sort of speculation in the

textbooks if it proves nothing. He replied, "No you don't. You want to

say that it is a primitive holdover."

Dr. Patterson said that Archaeopteryx "has simply become a patsy for wishful thinking." In a letter to this author dated April 10, 1979, Dr. Patterson said, "Is Archaeopteryx the ancestor of all birds? Perhaps yes, perhaps no. There is no way of answering the question." On the 1982 British television series mentioned earlier, Dr. Patterson emphasized the same point -- that Archeopteryx was not a good example of a transitional form. Figure 3. Archaeopteryx, the showcase of a transitional form, is now admitted by leading evolutionists not to be on the direct line between reptiles and birds because it is preceded by modern bird fossils. |

This kind of information would be most helpful if it were made available to public school, college, and university students when they attempt to unravel the great puzzle of which theory of origins they should use as the basis for their philosophy of life.

Dr. Fisher was asked, "Do you know anything about that, how feathers might

have arisen from scales?" He replied, "None whatsoever."

| Dr. Raup felt that the problem with Archaeopteryx was that our classification system forced us to put it in one box or the other. He said that if there were no intermediate category in our taxonomic system, our taxonomic tradition forced us to put something like Archaeopteryx in one class or the other. It was then pointed out to him, "But if it had half a feather, we'd be very glad to throw out the classification system. Nobody I've ever heard debating has ever used the ground rule that the only way we'll accept a transition is within the present classification system. Dr. Gish says it would take only five or six of these truly in-between forms with partial structures to document evolution. Anybody on either side investigating this thing, if they found a transitional form that had a partially formed or evolved organ or structure, would be very happy to say, 'You've got one for your side.' I would. I'm looking for that." Dr. Raup replied that, according to John Ostrom's current thinking about Archaeopteryx, in a sense the wings of Archaeopteryx were half-formed wings. |

|

A report in Science magazine, March 9, 1979, was then handed

to Dr. Raup with the comment: "This shows that the primary feathers (flight

feathers on wings) of Archaeopteryx were asymmetrical and identical

to those of modern flying birds. In non-flying birds such as the emu and

ostrich, the primary feathers are symmetrical. Thus, specialists say that

Archaeopteryx

flew.

That supersedes some of the earlier statements that it was just a dinosaur

with feathers."1

|

Dr. Raup replied, "Okay, I heard Ostrom talk about this at a lecture

series in Chicago. It is his contention that they were used for trapping,

not for flying but trapping."

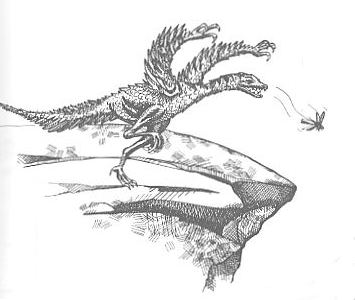

This is correct because Dr. John Ostrom of Yale University, a recognized world authority on the origin of birds, described his trapping theory in an article in the January/February 1979 issue of American Scientist magazine. He showed a sketch of a dinosaur that was growing wing feathers and using them for catching insects (see Figure 4). He felt that this was a much more plausible sounding scenario than the one about dinosaurs initially growing feathers as an insulation blanket.2 In 1982 the British Museum of Natural History in London included this insect-catching explanation in their display on the origin of birds. Figure 4. Evolutionists speculate that reptiles did not develop feathers initially for flying, instead, they might have invented them for some entirely different purpose such as for catching insects. |

One reason the insect-trapping pre-adaption scenario was invented was because of the publicity being given to the reptile-to-bird transition by those criticizing the gradualistic idea of evolution. As mentioned earlier, Schindewolf and Goldschmidt had first brought attention to the problems of gradualism when they tried to escape from the quandary by proposing that a reptile laid an egg and a bird was hatched from the egg -- twice in the same area and the same generation so there could be reproduction. Creationists drew much attention to the great difficulty evolutionists were having when they tried to invent plausible stories of how a reptile could have gradually developed the host of coordinated structures of birds.

This insect-catching scenario postulates that a population of dinosaurs gradually frayed out their foreleg and tail scales, somehow getting flight feathers with a rigid center shaft and hundreds of delicate parallel barbs running out from it. These contained thousands of little barbules to hook them together making an effective air seal. As the dinosaur dashed about in the underbrush chasing insects, it was able to keep these delicate new inventions from getting broken so that there was a selective advantage for the feathers to gradually become larger and larger. The dinosaurs with smaller foreleg feathers, according to the story, died off due to the competition for insects, leaving only those with large feathers to survive.

At the same time, the dinosaurs necessarily developed a host of other highly coordinated structures, that prepared it for flight. Then one day it must have found that it was all ready for its maiden flight: It had a foreleg that was shaped like an airfoil nicely streamlined with curvature in the proper direction to generate lift; its bones were hollow; its center of gravity was located precisely for perfect stability in the air (about 25 percent of the way back from the front edge of the foreleg); its scales had thousands of barbs and barbules all evenly hooked together to keep the air from leaking through; it had perching feet; the scales on its tail were also converted into feathers for steering and balance; it had somehow developed the intricate skill to coordinate the action of all of these structures in flight; then it took off and became a flying bird. So the story goes.

But, in the game of evolutionary speculation, nothing seems to endure

very long except the sacrosanct common-ancestry assumption. The scenario

of preadaption by trapping insects generated so much tongue-in-cheek comment

and outright embarrassment that others wrestling with the origin of birds

problem decided to change the story again. On July 1, 1983, Science

magazine

published an article by Roger Lewin about some work by a group at Flagstaff,

Arizona, that was supposed to have solved the whole problem. He made the

surprising statement: "Unlike other major hypotheses on the origin of flight...

there is no requirement for a leap of faith at any point."3

| The Flagstaff group had written a very simple mathematical model of a flying object. This looked most impressive to natural scientists and others not familiar with aerodynamics and the complexity of getting a non-flying animal into the air by its development of flapping flight through purely random processes. The main discussion was restricted to an argument about whether reptiles learned to fly by dashing along the ground and gliding or climbing up into a tree and jumping off like a parachutist. This work is not expected to make an enduring contribution to the field of testable science, and a person knowledgeable about the complexities of flight must puzzle over the statement. It is difficult to understand how scenarios that cannot be tested can be transformed into certainty without a "leap of faith" somewhere along the line. |

|

Even John Ostrom abandoned the insect-trapping story in 1983. The above-cited article by Roger Lewin in the July 1, 1983, issue of Science magazine quoted him as saying that he had given up on that idea. The last two lines of the article were: " 'Yes,' says Ostrom, 'the insect net idea is dead. It did its job.'" Apparently Ostrom felt that the job at hand was to convince the public and millions of students that birds had actually evolved from reptiles regardless of the fact that there was no scientific evidence of such a transition or any plausible mechanism for it.

For a year or so, Dr. Ostrom subscribed to the hypothesis that birds learned to fly by dashing along the ground, leaping into the air, and making short, gliding flights. Then after being shown that aerodynamically this would have been impossible, he joined the group who thought the first bird climbed up into a tall tree and parachuted to the ground.

Evolutionist author Francis Hitching included a detailed discussion of Archaeopteryx in his 1982 book, The Neck of the Giraffe -- Where Darwin Went Wrong.4Referring to the oft-repeated claim that this fossil bird "proved beyond any argument" that there existed an animal with both reptilian and bird features, he wrote that the case is not so unambiguous as the claims make out: "Every one of its supposed reptilian features can be found in various species of undoubted birds."

He discussed these six features of Archaeopteryx:

1. It had a long bony tail, like a reptile's.

In the embryonic stage, some living birds have more tail vertebrae than Archaeopteryx. They later fuse to become an upstanding bone called the pygostyle. The tail bone and feather arrangement on swans is very similar to those of Archaeopteryx. One authority claims that there is no basic difference between the ancient and modern forms: the difference lies only in the fact that the caudal vertebrae are greatly prolonged. But this does not make a reptile.

2. It had claws on its feet and on its feathered fore-limbs.

However, many living birds such as the hoatzin in South America, the touraco in Africa, and the ostrich also have claws. In 1983 the British Museum of Natural History displayed numerous species within nine families of birds with claws on the wings.

3. It had teeth.

Modern birds do not have teeth but many ancient birds did, particularly those in the Mesozoic. There is no suggestion that these birds are transitional. The teeth do not show the connection of Archaeopteryx with any other animal since every subclass of vertebrates has some with teeth and some without.

4. It had a shallow breastbone.

Various modern flying birds such as the hoatzin have similarly shallow breastbones, and this does not qualify them from being classified as birds. And there are, of course, many species of non-flying birds, both living and extinct.

Recent examination of Archaeopteryx's feathers has shown that they are the same as those of modern birds that are excellent fliers. Dr. Ostrom says that there is no question that they are the same as the feathers of modern birds. They are asymmetrical with a center shaft and parallel barbs like those of today's flying birds.

5. Its bones were solid, not hollow, like a bird's.

This idea has been refuted because the long bones of Archaeopteryx are now known to be hollow.

6. It predates the general arrival of birds by millions of years.

This also has been refuted by recent paleontological discoveries. In 1977 a geologist from Brigham Young University, James A. Jensen, discovered in the Dry Mesa quarry of the Morrison formation in western Colorado a fossil of an unequivocal bird in Lower Jurassic rock. This deposit is dated as 60-million-years older than the Upper Jurassic rock in which Archaeopteryx was found. He first found the rear-leg femur, and later the remainder of the skeleton. This was reported in Science News September 24, 1977. Professor John Ostrom commented, "It is obvious we must now look for the ancestors of flying birds in a period of time much older than that in which Archaeopteryx lived."5

At a conference in 1983, Professor Ostrom stated, "It is highly improbable that Archaeopteryx is actually on the main line (to modern birds)."6 It will be interesting to see if textbook writers begin to retract their previous dogmatic statements about Archaeopteryx being the best available showcase example of an intermediate form that documents the transition of one species into a basically different species with grossly different structures and functions.

In a debate in Tampa, Florida, Dr. Kenneth Miller stated that modern birds have little bumps, called nodes, on the wing bones where feathers are attached, but Archaeopteryx didn't have these so it was supposedly more reptilian than modern birds.7 This is a fallacious argument. It is true that some birds, like the robin and barn owl, have an easily detectable row of bumps along the aft side of the ulna wing bones. But it is also true that the bumps are much less prominent in other living birds like the screech owl and, in some, like the chicken, they are not visible at all. This argument is obviously impertinent since domesticated birds like the chicken are assumed to have been derived from wild birds which are supposed to have evolved from reptiles. Even schoolboys have learned that it is not difficult to become trapped in inconsistencies when you start making up stories.

Reptile to Mammal

Most books and museum displays on evolution state that mammals originated from reptiles with the insect eaters, called insectivores, being the first true mammals. Both the placental and marsupial mammals, they contend, evolved in parallel from the reptiles since they have such distinctively different reproductive systems.

There is a significant difference between reptiles and mammals. Reptiles lay eggs which have hard shells and they have scales on their skin. All reptiles have a double-hinged jaw with multiple bones in the jaw and a single bone in each ear. Mammals give birth to their young, have mammary glands, and have hair. They all have a single mandible or lower jaw that is hinged with a single joint on each side, and they all have three bones in each ear, commonly called the hammer, anvil, and stirrup. If the highly complex and integrated structures of mammals slowly and gradually evolved through mutations from the reptiles, the fossil record should show abundant evidence of the transformation.

Dr. Raup said that he knew nothing about the origin of mammals. He did not know of any evidence of this transition.

According to Dr. Patterson, some people say that the first mammals appeared in the Triassic, or they argue about Jurassic or Cretaceous and make up sequences for placental mammals, marsupials, etc., consistent with the story of evolution. But he could offer no fossil evidence that would support the stories. He acknowledged that the North American wolf and the marsupial Tasmanian wolf had comparable bone structures although they were assumed to have branched off from a common ancestor at the reptile stage.

When asked if he agreed that the first mammals were insectivores, Dr. Eldredge said that he had "no knowledge about that." Regarding the December 1976 National Geographic scenario on the origin of whales, he said that whales came out of some group of archaic ungulates.8 He had written a paper several years ago and pointed out that in making up such accounts one was only limited by one's "own imagination and the credulity of the audience," but it was still "just a scenario, just a story." As science, he added, "It doesn't wash." In other words, since evolutionary scenarios are not part of testable science, the only limitation that restricts these authors is the gullibility level of the public.

Dr. Eldredge was then asked about these scenarios: "That is Dr. Patterson's point. He says in this letter (April 10, 1979) to me that it is easy enough to make up stories, but he knows of not a single fossil or living transition. You've been quoted in the papers as saying something similar."

To this Dr. Eldredge answered, "Yes," and asked this author why the letter had been written to Dr. Patterson. The followingn reply was given: "Because the schools have been teaching some things that are misleading. When you dig into it you readily find this situation. Yet, teachers that I know of just present the whole thing as though it were fact. We want to try to sort out the fiction from the science."

To this Dr. Eldredge said, "I want to teach you something right now when you ask, is there not any part of evolution that is not a scenario?" He said that there were several things that people meant by evolution. There was evolution "supposed history," what he called the "actual sequence of events that took place in evolution." He slipped somewhat in calling it a supposition and then in the same sentence asserted that these supposed events actually took place. When asked if by this he meant viewing fossils, he replied that he meant comparing things that are alive today from an evolutionary point of view. In other words, he was saying that if you assumed that evolution actually occurred and then interpreted the similarities of organisms to be verification of this assumption, he called that "history." He said that the second aspect of evolution was the body of theory that purported to explain how it occurred, and the two should be kept separate.

He thought that some of the material about mechanisms could be scientifically

treated -- that it was open to a hypothetical deductive approach -- but

evolutionary history was an "entirely different kettle of fish." Scientists

were trying to analyze that pattern. He said that there are some people

who are fed up with this exact point about "imaginary stories" that have

been written about the nature of the history of life. Dr. Eldredge said:

I admit than an awful lot of that has gotten into the textbooks as though it were true. For instance, the most famous example still on exhibit downstairs (in the American Museum) is the exhibit on horse evolution prepared perhaps 50 years ago. That has been presented as literal truth in textbook after textbook. Now I think that that is lamentable, particularly because the people who propose these kind of stories themselves may be aware of the speculative nature of some of the stuff. But by the time it filters down to the textbooks, we've got science as truth and we've got a problem.

So Dr. Eldredge said emphatically that some of the evolution stories

printed in textbooks, like the one about the so-called horse series, are

"lamentable."

The great differences between the reptilian and mammalian masticatory apparatus as well as the differences between the ear mechanisms in these groups are major problems for evolutionists. All reptiles have seven bones in the lower jaw while all mammals, living or fossil, have a single jaw bone. Reptiles have a single bone in the inner ear while all mammals have three bones. Evolutionists contend that three reptile jaw bones on each side slowly migrated across the jaw joint up into the ear of the mammal, somehow replacing the single bone in the reptile ear. But there is no convincing scenario that can even be conceived for getting the jaw bones across the jaw joint.

A 1978 book, Evolutionary Principles of the Mammalian Middle Ear,

is

an authoritative treatment of the reptile-to-mammal transition relative

to the problem of the ear bones.9

The magazine

Evolution

carried a thorough review of this book. It

said:

These general statements about the evolution of the mammalian middle ear that appear are in the nature of proclamations. No methods are described which allow the reader to arrive with Fleischer at his "ancestral" middle ear, nor is the basis for the transformation series illustrated for the middle ear bones explained.... Those searching for specific information useful in constructing phylogenies of mammalian taxa will be disappointed.10

Indeed, there are absolutely no fossils showing the migration of

the jaw bones of the reptile up into the ear of the mammal.

Although the museum officials did not do so in their interviews, evolutionists

frequently offer the so-called mammal-like reptiles as intermediates between

the reptiles and mammals. There are hundreds of species of these creatures

that were contemporaneous with many other early reptiles. They offer no

solution for the reptile-to-mammal transition, for they all appeared abruptly

in the fossil record and even became extinct before the age of dinosaurs.

A 1982 article in New Scientist magazine gave a good picture of

the problem for evolutionists:

Each species of mammal-like reptile that has been found appears suddenly in the fossil record and is not preceded by the species that is directly ancestral to it. It disappears some time later, equally abruptly, without leaving a directly descended species.11

The picture has not changed since George Gaylord Simpson wrote Tempo

and Mode in Evolution

in 1944, when he said:

This is true of all thirty-two orders of mammals. The earliest and most primitive known members of every order already have the basic ordinal characters, and in no case is an approximately continuous sequence from one order to another known. In most cases the break is so sharp and the gap so large that the origin of the order is speculative and much disputed.

Later Simpson confirmed that this absence of transitional forms

was a systematic, universal phenomenon:

This regular absence of transitional forms is not confined to mammals, but is an almost universal phenomenon, as has long been noted by paleontologists. It is true of almost all classes of animals, both vertebrate and invertebrate... it is true of the classes, and of the major animal phyla, and it is apparently also true of analogous categories of plants.12

Roger Lewin wrote in Science magazine that the transition

to the first mammal "is still an enigma."13

But, then, this supposed transition should be no different than any of

the others.

Origin of Horses

Not only was there general agreement among the museum officials about the questionable nature of some of the scenarios made up in an attempt to explain the lack of fossil or living evidence to support macroevolution, but there was also agreement on the so-called horse series. This series, commonly shown in school textbooks, starts with a four-toed Hyracotherium, passes through several three-toed creatures, and ends with a single-toed modern horse. Dr. Patterson agreed that it was not really a series at all. Dr. Raup said that as more has been learned about the supposed evolution of the horse, more separate lineages have been recognized and it is far more complicated than early work indicated. He said that you do find lineages "on a small scale," but his museum's display omits the four-toed Hyracotherium completely and starts the display on horse evolution with a three-toed creature.

Horse evolution has been presented for many years in textbooks as a way to demonstrate how evolution has worked to originate a structure -- the single toe. The first such series involving four steps was made in 1874, and the famous American Museum display on horse evolution to which Dr. Eldredge referred was made up in 1905. The 1964 book Atlas of Evolution, by Sir Gavin DeBeer, Director of the British Museum of Natural History, shows a highly detailed ladder of horse evolution. 14 A current textbook used for Regents biology in New York State, Biology for You, includes sketches of the horse series as the only illustration of fossils of intermediate forms between species.15 But the people most familiar with the actual fossil evidence have a contrasting opinion about what the evidence indicates. Heribert-Nilsson says, "The family tree of the horse is beautiful and continuous only in the textbooks."16 Here are some of the reasons.

Nowhere in the world are the fossils of the horse series found in successive strata. When they are found on the same continent, like in the John Day formation in Oregon, the three-toed and one-toed are found in the same geological horizon (stratum). In South America, the one-toed is even found below the three-toed creature.17 And when other structures besides toes are considered, the picture does not look so impressive. For example, the four-toed Hyracotherium has 18 pairs of ribs, the next creature has 19, then there is a jump to 15, and finally back to 18 for Equus, the modern horse. The sequence requires arranging Old World and New World fossils side-by-side, and there is considerable dispute about the order in which they should be arranged. One specialist says, "The story depends to a large extent upon who is telling it and when the story is being told."

The four-toed Hyracotherium (now called Eohippus) does not look the least bit like a horse. When first found it was classified as Hyracotherium because, skeletally, it was said to be identical to the rabbit-like hyrax or daman that is running around in the African bush today. Eohippus fossils have been found in surface strata alongside two types of modern horses, Equus nevadensis and Equus occidentalis.18 The series shown in museum displays generally depicts an increase in size, and yet the range in size of living horses today from the tiny American miniature ponies to the enormous shires of England is as great as that found in the fossil record. It is no wonder that Dr. Eldredge called the textbook characterization of the horse series "lamentable."

When scientists speak in their offices or behind closed doors, they frequently make candid statements that sharply conflict with statements they make for public consumption before the media. For example, after Dr. Eldredge made the statement about the horse series being the best example of a lamentable imaginary story being presented as though it were literal truth, he contradicted himself. The morning of the beginning of the Seagraves' trial in California he was on a network television program. The host asked him to comment on the Creationist claim that there were no examples of transitional forms to be found in the fossil record. Dr. Eldredge turned to the horse series display at the American Museum and stated that it was the best available example of a transitional sequence. On February 14, 1981, Sylvia Chase, host of the ABC Television program "20/20," questioned him on this subject as follows:

Sylvia Chase: "Dr. Niles Eldredge, Curator of the Department of Invertebrates of the American Museum of Natural History, is one of many scientists vigorously opposed to the Creationists. I asked him for evidence (for evolution)."

Dr. Eldredge: "Ahh, the horse is a good example. Here's an effectively modern horse which is a million years old, but we can all recognize it as a horse. And as we go deeper in lower layers of rock, back further in time, we excavate successively more primitive horses. Here's one that is two million years old. They are becoming less and less obviously horse-like till we get back 60 million years ago, and here is the ancestor of the rhinoceros -- or very close to the ancestor of the rhinoceros. So when the Creationists tell us that we have no intermediates between major groups, we point to a creature like the dawn horse and say, 'Here we have 60 million years ago an exact intermediate between horses and the rhinos.' " So in 1981, after joining the anti-creationist campaign, Dr. Eldredge repeated a scenario for a nationwide audience that in 1979 he had called "lamentable."

Neck of the Giraffe

Charles Darwin devoted nearly a page in The Origin to a scenario that attempted to explain the origination of the neck of the giraffe. Although generally criticizing Lamarckism, in certain cases he accepted as an evolutionary mechanism the idea that offspring could inherit characteristics that the parents had acquired during their lifetime (Larmarckism). Using this idea, he speculated that the giraffe got its long neck by stretching higher and higher to reach leaves on trees as vegetation gradually dried up during a drought. There was more food on the highest branches and the least competition for them. The long neck was passed on to offspring. Today, however, the neck of the giraffe is commonly given as the classic example of how wrong Lamarck was.

It is not usually pointed out that the giraffe actually is an excellent example of how genetic principles restrict the amount of variation possible within mammals. Although a male giraffe may grow to about 20 feet tall, it has no more vertebrae in the neck than most other mammals, including man. The seven cervical vertebrae are simply elongated as are its legs.

It is speculated by neo-Darwinists that some ancestor of the giraffe gradually got longer and longer bones in the neck and legs over millions of years. If this were true, one might predict that there would either be fossils showing some of the intermediate forms or perhaps some living forms today with medium-sized necks. Absolutely no such intermediates have been found either among the fossil or living even-toed ungulates that would connect the giraffe with any other creature. Evolutionists cannot explain why the giraffe is the only four-legged creature with a really long neck and yet everything else in the world survived. Many short-necked animals of course existed side by side in the same locale as the giraffe. Darwin even mentioned this possible criticism in The Origin but tried to explain it away and ignore it. Furthermore, it is not possible for evolutionists to make up a plausible scenario for the origination of either the giraffe's long neck or its complicated blood pressure regulating system. This amazing feature generates extremely high pressure to pump the blood up to the 20-foot-high brain and then quickly reduces the pressure to prevent brain damage when the animal bends down to take a drink. After over a century of the most intensive exploration for fossils, the world's museums cannot display a single intermediate form that would connect the giraffe with any other creature.

Origin of Elephants

Both the British Museum and American Museum of Natural History have displays that show the various types of elephants in a series, from one with short tusks and a long lower jaw to one with long tusks and a short lower jaw. But nowhere can be found an intermediate form that connects the elephants with a basically different creature. These institutions do display an elephant with tusks projecting from the lower jaw, but that doesn't solve the problem; it just creates another one. The first elephant in the series is clearly an elephant.

Origin of Primates

The first clue to the origin of the group of mammals in which man has been placed regards the orientation of the eyes. Man is classified as a primate along with apes, New World monkeys, Old World monkeys and prosimians (tarsiers, lemurs, and tree shrews). All of the other primates have their eyes pointed forward, giving them binocular vision, however, the tree shrews have side vision as do the non-primates such as dogs or deer.

The popular scenario for the origin of primates speculates that when animals climbed up into trees and started jumping from branch to branch, only those survived that had their eyes pointed forward so they could see better to catch the branches. Those with side vision were less fit in the trees. So museum displays show a lineage of the tree shrew followed by the tar-sier with huge forward-facing eyes. But there is no fossil evidence of such a transition, for the shrews are distinct from the tarsiers. Furthermore, the reasonableness of the scenario seems questionable when it is given some thought. Squirrels have side vision, but they exhibit no less capability of seeing the next branch when jumping about in the treetops than do the monkeys with binocular vision. At least they are not commonly known to miss and fall out of trees. The first shrews found as fossils are clearly shrews, and there is no fossil evidence connecting them with any creature with binocular vision.

The tarsiers have eyes located in the front of the skull, thus giving them binocular vision, but the first tarsiers are 100 percent tarsiers. The same is true with both the broad-nosed New World monkeys and the narrow-nosed Old World monkeys. The book, Primates, says that the origin of New World monkeys is obscure and even less is known about the Old World monkeys.19 They appear abruptly in the fossil record as do the orangutans, chimpanzees, and gorillas.

In the Hall of Primates at the American Museum of Natural History, a mural fills one end of the display room. It was created by Dr. Eldredge to show the family tree of man and the other primates. A three-color code is used to indicate where the tree is based on actual fossils and where it is based on speculation. Portions of the tree shown in brown color represent reasonable guesses only. The tan portions are for "no fossils known" and the yellow sections represent actual fossils. It is especially significant that at every single fork in the tree, there is a brown and tan section indicating that it is based on guesses only without any actual fossil evidence.

Of the five natural history museum officials interviewed, Dr. David Pilbeam had the most expertise in the field of paleoanthropology (the study of fossil man) since he had worked specifically in this area for many years. He came to the attention of the scientific community as being an objective scientist when he wrote an article for Human Nature magazine, June 1978, entitled, "Rearranging Our Family Tree." In it he reported that discoveries since 1976 had shaken his view of human origins and forced a change in ideas of man's early ancestors. His previous views were wrong about tool use replacing canine teeth, evidence for which was totally lacking. He did not believe any longer that he was likely to hit upon the true or correct story of the origin of man. He repeated a number of times that our theories have clearly reflected our current ideologies instead of the actual data. Too often they have reflected only what we expected of them.

In his interview, Dr. Pilbeam elaborated on the subjects he had discussed in his 1978 article. Currently he was teaching a course that covered primates and was also doing field research in Africa and Pakistan. He was advising the Kenya government on the establishment of an international institute for the study of human origins. His office was near those of anthropologists Richard Leakey and his mother, Dr. Mary Leakey, in Nairobi, Kenya. He referred to several more recent publications, a review article in Annual Reviews of Anthropology, and several on his work in Pakistan.

Why had he changed his position on human origins? He said that it was not due to the discovery of only one particular specimen, but the recovery of various materials made him realize that his previous statements, which had been made so adamantly, were really based on very little evidence. He began to wonder, since they were based on so little evidence, why he had held them so strongly. It made him think about the nature of scientific thinking, and this precipitated a very profound change in his approach to analyzing data. He said that many of the statements made in the field of human origins had "very little to do with the real data and a great deal to do with unstated assumptions." He thought that this was true not only of his field but, "Much of what is said in other areas, I think, is also highly speculative."

Dr. Pilbeam said that there were two ways to look at evolutionary theory: the punctuated way and the gradual way. Before the punctuated equilibria theory came along, scientists said emphatically that there was only one way. Dr. Pilbeam thought that it would be very difficult to tell for most mammal groups which alternative was correct, but he thought that some people who disagreed with punctuated equilibria theory did so on philosophical rather than empirical grounds. He emphasized that this was why he had made such a point in his 1978 article that one's preconceived notions shape the way one perceives data.

Dr. Patterson agreed about the lack of fossil evidence connecting man with a lower primate. In answer to the question, "What do you think of the Australopithecines as man's ancestors?" Dr. Patterson replied, "There is no way of knowing whether they are the ancestors to anything or not."

So, the museum officials who were in an excellent position to know about the fossil evidence relating to the origin of man had very little to say about the subject. If any actual fossil evidence existed showing how man could be connected with any other primate group, it is unlikely that they would have kept silent about it.

Richard Leakey summed up the situation on the final Walter Cronkite Universe program. He said that if he were going to draw a family tree for man, he would just draw a huge question mark. He said that the fossil evidence was too scanty for us to possibly know man's evolutionary origin, and he did not think we were ever going to know it.

William R. Fix has written a book, The Bone Peddlers, in which

he examined in great detail what the most prominent evolutionary paleoanthropologists

have said about each of the various fossils that have been claimed to show

evidence of man's ancestry. He showed how further studies and more recent

discoveries have eliminated each of man's supposed ape-like ancestors from

his family tree. He wrote:

The fossil record pertaining to man is still so sparsely known that those who insist on positive declarations can do nothing more than jump from one hazardous surmise to another and hope that the next dramatic discovery does not make them utter fools. . . . Clearly, some people refuse to learn from this. As we have seen, there are numerous scientists and popularizers today who have the temerity to tell us that there is "no doubt" how man originated. If only they had the evidence....I have gone to some trouble to show that there are formidable objections to all the subhuman and near-human species that have been proposed as ancestors.20

Mr. Fix expresses his preference for evolution theory over that

of creation, but he insists that his fellow evolutionists have been playing

loosely with the rules of science and have conveniently overlooked the

contradictory evidence:

So, when it comes to the fossil record, or any other body of evidence, for the sake of the good cause they accentuate the supportive data and ignore or minimize as far as possible the contrary indications.21

Are There Any Documented Transitional Fossils?

None of the five museum officials could offer a single example of a transitional series of fossilized organisms that would document the transformation of one basically different type to another. Dr. Eldredge said that the categories of families and above could not be connected, while Dr. Raup said that a dozen or so large groups could not be connected with each other. But Dr. Patterson spoke most freely about the absence of transitional forms.

Before interviewing Dr. Patterson, the author read his book,

Evolution,

which

he had written for the British Museum of Natural History.22

In it he had solicited comments from readers about the book's contents

and a letter was written to Dr. Patterson asking why he did not put a single

photograph of a transitional fossil in his book. On April 10, 1979, he

replied to the author in a most candid letter as follows:

I fully agree with your comments on the lack of direct illustration of evolutionary transitions in my book. If I knew of any, fossil or living, I would certainly have included them. You suggest that an artist should be used to visualize such transformations, but where would he get the information from? I could not, honestly, provide it, and if I were to leave it to artistic license, would that not mislead the reader?I wrote the text of my book four years ago. If I were to write it now, I think the book would be rather different. Gradualism is a concept I believe in, not just because of Darwin's authority, but because my understanding of genetics seems to demand it. Yet Gould and the American Museum people are hard to contradict when they say there are no transitional fossils. As a paleontologist myself, I am much occupied with the philosophical problems of identifying ancestral forms in the fossil record. You say that I should at least "show a photo of the fossil from which each type of organism was derived." I will lay it on the line--there is not one such fossil for which one could make a watertight argument. The reason is that statements about ancestry and descent are not applicable in the fossil record. Is Archaeopteryx the ancestor of all birds? Perhaps yes, perhaps no: there is no way of answering the question. It is easy enough to make up stories of how one form gave rise to another, and to find reasons why the stages should be favored by natural selection. But such stories are not part of science, for there is no way of putting them to the test.

So, much as I should like to oblige you by jumping to the defense of gradualism, and fleshing out the transitions between the major types of animals and plants, I find myself a bit short of the intellectual justification necessary for the job.

In his interview several months later, Dr. Patterson was asked to

elaborate, "You stated in your letter that there are no transitions. Do

you know of any good ones?" He replied, "No, I don't, not that I would

try to support. No." Throughout the interview he denied having transitional

fossil candidates for each specific gap between the major different groups.

He said that there are kinds of change in forms taken in isolation but

there are none of these sequences that people like to build up. Putting

it as a question, he said, "If you ask, 'What is the evidence for continuity?'

you would have to say, 'There isn't any in the fossils of animals and man.

The connection between them is in the mind.' "

Did he "know of any documented evolution going on today in the macro sense where we're looking for a new structure that previously did not exist -- like an arm forming?" He answered, "No, not of an arm forming, not in the macro sense." Then he was asked, "Then you know of no structure that you could classify as developing and not fully functional?" Reply: "No." It was noted that some authors are claiming that there is no real evolution going on today other than minor variations like the shift in coloration in moths. He said that he would have to agree; he did not know of any either. What did he see as the biggest problem with the concept of evolution? He said that it was a philosophical problem. People seem to find the evidence they are looking for. He did not think it was possible to find the answer to origins in science: "There are solutions to problems in science but I don't think this is science we are talking about, I think it's history." With this perceptive statement there can be no rational argument.

Such devastating statements do not, however, seem to affect the faith of hard-line evolutionists. They just make up stories to explain them away. For example, philosophy professor Philip Kitcher, a well-known apologist for evolution-only teaching, gave this attempted explanation for Dr. Patterson's letter in a television debate with the author May 3, 1984. The host asked the evolutionists, "The fact that there are no transitional fossils at the British Museum -- why would this fellow write this letter?"

Dr. Kitcher replied:

Dr. Patterson, when he wrote that letter in 1979, he wrote that letter in complete ignorance of the political situation in the USA. He thought that he was writing a letter to a fellow professional scientist.... When people like Dr. Patterson have disagreements with their professional colleagues, these things are torn out of context by creation scientists.

Thus, Dr. Kitcher tried to discount Dr. Patterson's devastating

statements in his letter by inferring that he would not have been so truthful

if he had known of the great public controversy in the USA over how theories

on origins should be taught. This aspersion on Dr. Patterson's character

is without foundation, for Dr. Patterson repeated the same points and made

even stronger statements in his interview with the author several months

later. This was after he had been told of the situation in public education

in the USA and a month earlier had been given two creation-science books

to read. They were: Evolution? The Fossils Say No! by Gish23

and The Creation/Evolution Controversy by Wysong.24

In the interview he explicitly said that he knew of no transitional fossils

and that evolution was based on faith alone.

Did Dr. Fisher know of any transitional forms between the higher taxa? He replied, "Intermediates within families and even within orders, but not between phyla. Nor do I think you will ever find any between phyla." Why? His only answer was the standard one -- the imperfection of the fossil record. "You can either say that there are no transitional forms, or you can say that because of the vagaries of preservation, only one in ten million of this particular species was ever preserved." That would add up to a heap of fish considering the billions that were preserved in the Lompoc formation alone! One is forced into the most ridiculous positions when making up stories to explain why the fossil record falsifies the theory of common-ancestry evolution.

In his 1979 interview with the author, Dr. Eldredge was much more candid about the lack of ancestors in the fossil record. He said, "I've got problems with ancestors, too. That's why when I work with the history of life I'm with guys like Patterson." He said that all he tried to do was chart the nested sets of resemblances and arrive at the least objectionable sort of theory about how things were related in a general sort of way. He said that he made "no definite statements about who was ancestral to whom." Then in 1981 he repeated a scenario for a nationwide audience that in 1979 he had called "lamentable," and he claimed that Eohippus was "an exact intermediate" between the horses and the rhinos.

He did say in 1979 that when you were working at the species level you could find ancestors and descendants. But when asked, "Isn't it more than at the species level?" he responded, "No, just among species, that's all." It was pointed out that some people say that maybe families can be connected and he replied, "They are wrong. How can a family evolve?" He said that what we think we know about evolutionary mechanisms is that natural selection, working on natural variation within species, brings about the origin of new species which bud off from the old communities. You take these lineages and put them together in larger and larger groups but those groups do not have the same ecological existence that species have. So, he said that his position and that of others was that "species are real units in nature." He said, "The genera, families, etc., even if they are smaller lineages, don't exist in the same sense as a species. They only evolve as their component species do. Therefore, the idea of a family being ancestral to another family is illogical. It never happens."

This is a rather confusing explanation of why there are no transitional forms to be found either among the living or fossilized organisms. If every living organism had an ancestry that consisted of an unbroken lineage connected to a single-celled organism, it should make no difference whatsoever if man has decided to call the various stages along the way by different names. Just as the organisms within a species can be connected, so should the different species, genera, families, orders, classes, and kingdoms be shown to be connected. That is a specific prediction that obviously should be made from the theory of common-ancestry evolution if it were a truly scientific theory. If all life had a common ancestor, how could it be "illogical" for one family to be ancestral to another family?

Every organism in the continuum between a single cell and man is a member of one of the various families. Webster's dictionary says that "ancestral" means "derived from an ancestor." Since the theory of evolution, as Dr. Eldredge speaks of it, holds that all life came from a common ancestor, there is no conceivable way that the English language could be distorted to permit one to correctly state that no family could be ancestral to another family. Certainly some lower family should be ancestral to every higher family if evolution actually occurred.

The author made the following reply to this statement by Dr. Eldredge: "Somehow the family that dogs or cows are in had to arise. You think there are transitions at the species level, but do you know of any at a higher level? That is really what it is all about when you get down to it. Where did even a vertebrate come from? That would be easy to recognize."

Dr. Eldredge replied that if you took cats and dogs, the closest that he would ever put it was that you had two separate families and the closest relative was some other one like, say, hyenas. Hyenas (Hyaenidae) and cats (Felidae) are the closest relatives because they might share some similarities that are not shared with any other group. He concluded, "Now you might suspect that you have the ancestor by this line of reasoning." He also used the example of the supposed human ancestor, Australopithecus africanus. The skull of that was very difficult to assess for he had tried and tried when he was working as an anthropologist to find a particular feature that would have allowed him to say that it shared a specialized resemblance with, say, Australopithecus robustus as opposed to Homo habilis. He said that some people say, "Ah ha! It's an ancestor." But he said that he did not know if it was an ancestor or not. He said, "There is no way to really come to grips with it logically."

Dr. Eldredge should have stated that there was no logical way to harmonize

the scientific evidence with the theory of common-ancestry evolution since

no connections between any basically different groups of organisms could

be documented with fossils. He did not mean that it would be impossible

to connect families if evolution were true. He meant that there was no

way to connect them using either fossil or living evidence.

|

GRADUALISM REPLACED BY THE HOPEFUL MONSTER THEORY

What did Darwin say about the lack of transitional forms in the fossil record? This lack actually gave him great concern, and he wrote an entire chapter in The Origin about it. Generally, he explained the absence away with the argument that these forms just were not fortunate enough to have become fossilized, and there had not been enough geological research done by 1859. For some reason, Gillespie did not think this was explaining away the evidence when he wrote, "Darwin's analysis of the fossil record then was not an ad hoc 'explaining away' of an embarrassing absence of evidence, but a revealing of how unreasonable it was to demand that evidence because of the nature of geological processes and the youth of paleontologi-cal science." And later he explained, "As shown, the absence of transitional forms in the fossil record had long been one of the strongest arguments against transmutation (common ancestry). In the 1861 edition of The Origin, Darwin enjoyed reporting that the 'assertion' that 'geology has yielded no linking forms ... is entirely erroneous.' "25 It is strange that, after over a century of searching for the linking forms, the world's greatest fossil museums have not been able to find them, unless perhaps, they do not exist. |

|

Origin of Plants

The origin of plants appears to be a complete mystery to evolutionists.

It is difficult to find even a postulated family tree of plant life. Dr.

Patterson said that he had seen a lot published on the origin of plants,

"Although I would agree that they are not convincing."

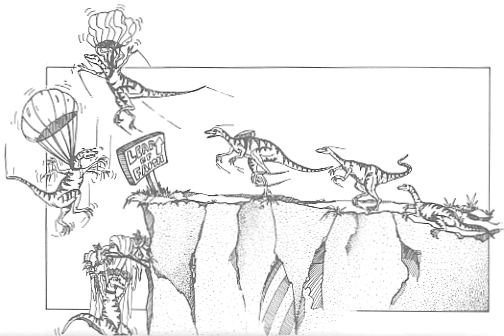

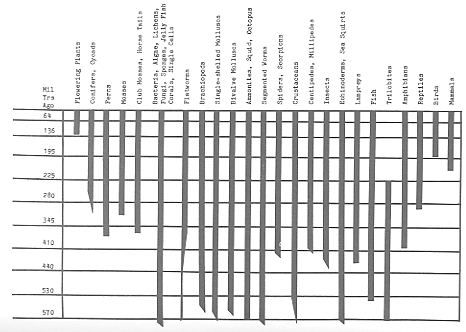

Dr. E.J.H. Corner of the Cambridge University botany school made a candid evaluation of the knowledge about plant evolution: "Much evidence can be adduced in favor of the theory of evolution -- from biology, biogeography, and paleontology, but I still think that to the unprejudiced, the fossil record of plants is in favor of special creation."26 In the book The Evolution of Life, E.C. Olson said: "A third fundamental aspect of the record is somewhat different. Figure 5. The actual fossil record shows the abrupt appearance and extinction of basic different life forms with no intermediate forms connecting them. It depicts sudden appearance and stasis. |

|

Many new groups of plants and animals suddenly appear, apparently without any close ancestors. Most major groups of organisms -- phyla, subphyla, and even classes -- have appeared in this way." He said that this is usually explained away by the argument that the fossil record did not record the intermediates, but, "Some paleontologists disagree and believe that these events tell a story not in accord with the theory and not seen among living organisms."27

Today many scientists are abandoning gradualistic evolution because

of two undeniable characteristics of the fossil record: the abrupt appearance

of new basic types of organisms followed by little or no change. The emerging

paleontological picture is shown in Figure 5 (above) which is based

on a similar diagram recently published in BBC's Life on Earth28and

Evolution

from Space by Fred Hoyle and Chandra Wickramasinghe.29

|

|

|

|

|